Seagull 1963: A Guide To The Other "Oriental" Watch

All subscribers welcome

If you’ve spent any time hanging around Avoidable Contact Forever that you know that “Made In The USA” is one of my primary obsessions. I believe that buying from local manufacturers helps your neighbors, shortens supply chains that have become increasingly fragile, helps the environment, and imparts a sense of decency and dignity to our daily existence. When that’s not possible, I try to buy from Western countries and/or Japan, as they generally offer decent working conditions and fair wages. Beyond that, I will jump through any number of absurd hoops to avoid buying and using Chinese products.

So with all that in mind… why did I spend a full $406.60 on a Chinese watch? The answer: because it is authentically Chinese, and horologically important. If you don’t care for the philosophy of this, and just want to know how, where, and why to buy a decent Seagull, skip the next eight paragraphs and you’ll be good.

Story from a Seagull

The story of the Seagull begins in Switzerland. There were three manufacturers of hand-wound chronograph movements in the post-WWII era. (The automatic or “perpetual” chronograph didn’t exist.) First off, you had Valjoux. Their hand-wound 72 movement, which beat at a leisurely 18,800 per hour and had just 17 jewels. That was the movement in all the original Rolex Daytonas, which were hand-wound Valjoux 72s well into the Seventies. Then you had Lemania, which supplied chronographs to several manufacturers and was about as well-regarded as Valjoux most of the time. Lemania’s engineering made it into the original Omega Speedmaster “Moonwatch”, with Caliber 321.

Last and least, there was Venus, which supplied Breitling and a bunch of now-forgotten brands. To finance the production of their new low-cost automatic chronograph movement, they sold the entire production line and machinery for their hand-wound 17-jewel Caliber 175 to the Tianjin Factory in mainland China. Unfortunately it wasn’t enough, and they were bought out by Valjoux in 1966. Not before having the last laugh, because Valjoux rebranded the low-cost, lever-operated Caliber 188 chronograph as the “Valjoux 7730”. The 7730 and its successors have been used in everything from Sears Roebuck “Tradition” chronographs during the early Seventies to $20,000 watches from IWC and other Swiss brands.

In 1966, the Tianjn factory made 1,400 watches for the Chinese (People’s Liberation) Air Force using a modified 19-jewel version of the Venus movement labeled ST19. This watch was never called a Seagull. Instead the Seagull name comes from a series of Chinese-engineered calibers and watches exported from 1973 forward. You can still buy all sorts of entirely Chinese watches under the Seagull name. The “Air Force Watch” was later replaced by quartz watches, as you’d expect, and the Venus equipment was mothballed.

In 2003, Tianjin resurrected the ST19 movement and in 2005 they began selling it as the “Seagull 1963”, referring both to the only Chinese watch name anyone outside the country knew and the year when the first Air Force Watch was prototyped. This watch has proven to be very popular in Europe because it’s basically a Sixties Swiss chronograph frozen in time, built the same way as Venus built them 60 years ago and using the more complex column-wheel chronograph movement instead of the lever-action with which Valjoux conquered the world. There have been some improvements, including raising the jewel count yet again to 21 or 22, depending on version, but this is fundamentally a new-old-stock Venus chronograph.

Therefore, the “Airforce Chronograph” is authentically Swiss, because it’s made by legitimately purchased Swiss machines and the Swiss process. But it’s also authentically Chinese, because it contains improvements designed at Tianjin and because it has a Chinese-designed case. It’s not a copy of anything. Not a fake Rolex. Doesn’t try to look like anything else, and never did. It has a real military history, just like IWC and Laco pilot’s watches or the Omega Speedmaster Flight Qualified. Nobody outsourced it. Unlike Nike and a hundred other American companies that decided to become mere importers from China, Tianjin is locally owned and operated. In watch-nerd terms, the ST19 is a manufacture movement, just like the in-house movements from Rolex, Omega, and Seiko. And without Tianjin and its Venus deal, the Valjoux 7730 wouldn’t exist.

Seagull, Red Star, And Fakes

Tianjin Watch Factory continues to sell watches under the Sea-Gull (stylized) name. Their 22-jewel reissue is made entirely in Tianjin using a variant of the original ST19 movement. It’s not cheap: the basic 1963 reissue is $799 with a steel case and strap. Real Sea-Gull 1963 Tianjin reissues are rare on the ground. They aren’t available all the time, they hew fairly closely to the Air Force original, but they are very nice by all accounts.

About a decade ago, a fellow named Thomas Leung left Tianjin and began making watches at a new factory called “Red Star” outside Shenzen. The photos you see in this article are of the Red Star factory. He builds his “Seagull 1963” watches using a Tianjin movement but with cases and crystals of his own design. He’s also commissioned custom ST19 movements with moonphase, calendar, and other complications. Red Star is sold via Poljot in Europe and Seagull 1963 in the USA through a Belgian importer. These are licensed variants and contain real Tianjin movements.

Since this is China, there are also plenty of ‘alternate’ Seagulls out there. Some use the original ST19 movement, which is available in bulk from Tianjin because one of Tianjin’s original duties in China was to produce standardized movements for casing elsewhere across the country. Remember that there’s still a bit of central planning going on in that country. Other “Seagulls” are just flat copies created entirely elsewhere, using movements created elsewhere that may have nothing to do with the original ST19. Supposedly you can walk through a bazaar in China and find quartz Seagulls, 42mm Seagulls, anything the mind can conceive.

Worth buying and wearing?

After all sorts of overthinking on the subject, I ended up getting a Red Star via the Belgian dealer, for two reasons:

I’d rather pay $406 for a brass Chinese chronograph than $799 for a steel one;

Brother Bark has a Red Star which looks quite nice and has served him well.

I think the Red Star is authentic enough, containing a Tianjin movement and being built in a clean room by someone who was there for the 2003 reissues. Those are my arguments for the authenticity of the “Seagull 1963”. But is it a good watch?

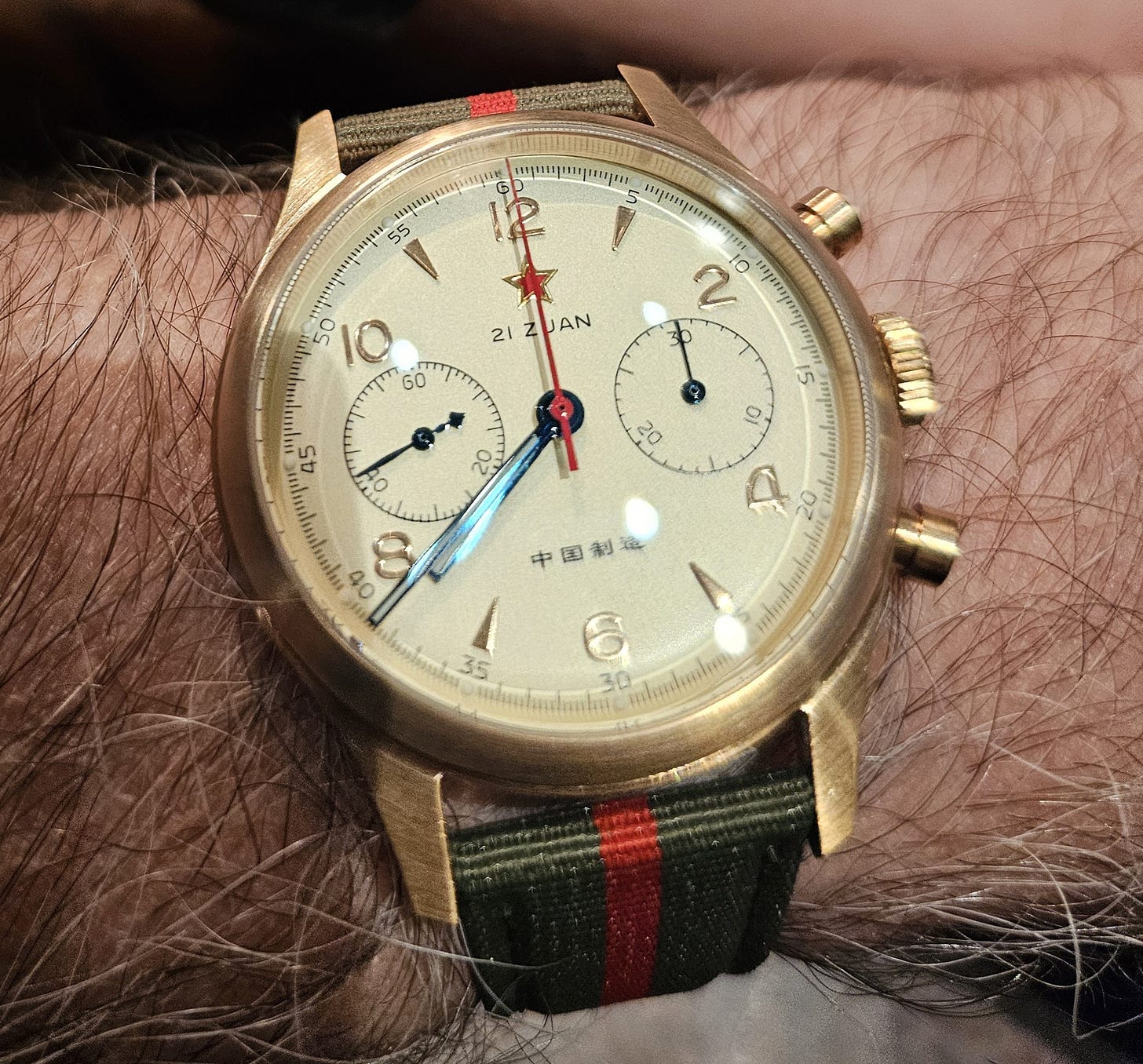

The bronze-cased 40-millimeter version I bought is certainly a pretty watch, if you dig that sort of thing. To the modern eye it’s about halfway between a sports chronograph like a Daytona and a dress chronograph like an Omega DeVille.

It’s clearly built with care. The controls work smoothly and reliably. It stays within about five seconds a day of the actual time, which is slightly better than the standard Rolex lists for its “Superlative Chronometer” label but not up to the standard of a Omega or Tudor “Master Chronometer” and light-years away from the zero-seconds-per-month gain or loss of my Grand Seiko Evolution 9 Spring Drive.

All the research I’ve done suggests that the ST19 movement is ultra-durable in operation. It’s much easier to find people griping about their Rolexes breaking than it is to find people whose Seagulls have given out in use.

This 40mm watch wears exceptionally well on my slightly-above-seven-inch wrist. It’s low profile and I have yet to strike it hard against anything the way I’ve repeatedly done with my Tudor Black Bay and IWC Ingenieur watches, both of which are much higher off the wrist surface. It ticks quietly and charmingly. It’s also the cheapest bronze mechanical watch of which I’m personally aware — but it doesn’t look like that. In terms of pure wrist appeal and visual quality, I think it’s as good as most Swiss watches. Certainly equal to a TaG or Oris, both of which I’ve owned in the past.

So let’s call it about the best $406 watch money can buy…

Wouldn’t you really rather have a Seiko?

…except Seiko offers quite a few made-in-Japan mechanical watches in the Seiko 5 line that are also very good. I own a few Seiko 5s, including the new SKX-GMT that can be had for $400 or less as a fully Japanese-sourced GMT!

I was also bullied by Brother Bark into finally buying the modern Prospex SPB121 “Alpinist” from Greentoe at a remarkable price of $450 against the typical discount price of $590-650. The Alpinist is a very special piece, it’s beautiful, and it’s the nicest watch that a lot of very smart people have ever bothered to buy:

What I’m going to suggest, however, is that these watches are not direct Seagull competitors. Seiko’s 4R and 6R movements, as seen in the SKX and Alpinist respectively, were designed from the jump to be affordable devices using stamped steel and low-cost materials. They work very well, but there’s no surprise-and-delight about them. The same is true of the cases and general workmanship. Good but not special.

In terms of general finishing, construction, design, and operation, the Seagull is conceptually closer to something like a vintage Heuer or Breitling chronograph than it is to an almost entirely machine-produced Seiko. It’s a “nicer” watch overall. So the Seagull vs. Seiko discussion mostly boils down to what you want out of a $400ish purchase. Do you want the most reliable mechanical timekeeping, with a warranty that can be honored in most major cities and via overnight US mail in all cases? Get a Seiko. Are you frustrated at the idea of sorting through different factories and fakes and importers? Get the Seiko.

If, on the other hand, you want something that you won’t see on someone else’s wrist most days of your life, something that represents an admirable collaboration between the best parts of two different cultures, plus something that looks and feels undeniably vintage, then the Seagull is worth the hassle. It can stand forthright comparison with a lot of much more expensive watches. There’s nothing fake or imitative about it. Short of finding a Sixties Swiss chronograph at a jeweler somewhere, this is as close as you’ll get to something that travels in time both forward at 21,600 beats per hour and backwards to an era where Swiss mechanical watches were simply tools for serious men. Mine is not for sale, and won’t be.

I have one of both, a modern but not automatic Speedmaster Moonwatch and one of these Seagulls. The difference in operation of the cam-and-lever Omega and the column-wheel Venus is night and day. I was very positively surprised by the little cheapie. I will be selling it soon because for some unexplainable reason I've bought the bigger case, and the 40mm Seagull looks too clunky next to the Speedmaster. I will get a 38mm Chinese to better match... it used to be a sign of excellence of how _small_ you could make a watch.

On a different but relevant note, I was recently on a watchmaking course since I have some older pieces that need servicing, and who the heck has $500 to spend on making a $50 "Wehrmachtwerk" work again? Well, the topic of old vs new came up inevitably and the old(er) expert told us something interesting. You look at some of these vintage movements that only have 10 or maybe 13 rubies, the rest of the train is running in steel bushings since 60 years. Wear? Minimal. How is this possible? Well, the Swiss manufacturers in the 50s were using the best materials, full stop. Tiny pivots (talking about .1mm) were hand burnished, bushings reamed to work-harden them so they don't wear. Nowadays the pivots are chemically hardened that gives an almost glass-hard surface, but it also makes them brittle. So you bump your sparkly new Rolex against a doorframe and it has the same chance of breaking its Paraflex-cushioned balance as a 1955 Junghans that had the basicest of basic shock protection.

BTW, did you get a GS maneki-neko in Ginza? Or just posted the photo to stories?

"Wouldn't you really rather have a Seiko?"

Well, yes, but I am extremely biased...