Guest Post: "Test Tracks #4", by John Marks

Free for all subscribers

(The story so far: Test Tracks #1 — Test Tracks #2 — Test Tracks #3)

Here are additional selections from the audio tracks I often use for the subjective evaluation of drivers and loudspeakers. (I have been listening to some of these tracks for well over 30 years.) The theme of this list is Diverse Music: Large-Scale Soundscapes (Part 2).

These tracks present unamplified music being played in a performance venue (or a studio that once was; or, which could do double-duty as, a performance venue), rather than in a typical acoustically-dead recording studio of today. Moreover, as far as I know, with no added reverberation.

These tracks are available on Qobuz and Tidal playlists:

QOBUZ: https://play.qobuz.com/playlist/14854373

TIDAL: https://listen.tidal.com/playlist/dd126c8c-f924-495f-92c6-d04b05c8162e

Of course, for many of the albums these tracks come from, you can shop on eBay or on Discogs.com for the LPs or CDs.

Please note: To its credit, Qobuz does not “normalize” the volume level of its tracks; therefore, you might have to adjust the volume levels as you go. If you listen on Tidal, you might wish to check your Account’s Settings, and defeat “Loudness Normalization” if necessary.

1 - 3. “O Fortuna,” from Fortuna Imperatrix Mundi: from Carmina Burana (Carl Orff).

“O Lady Luck, how Fickle thou art!” might serve as a poetically “free” translation of the Latin title of the first of Carl Orff’s massive musical settings of Medieval poetry. Poems which, like lots of poetry down through the ages, decry Fate’s cruelty, celebrate the rapture of love, and meditate upon our inevitable mortality.

Orff’s Carmina Burana (which means “Songs [or Poems] from the Beuern monastery”) has very little in common with the three centuries or so of classical music that came before Orff wrote it. It also has little in common with 20th-century “Modern” music. “Neo-Primitive” is the best description I have seen for Orff’s attempt to convey the rough-hewn spirit of the Medieval poetry by avoiding polyphony, harmonic complexity, and rhythmic subtlety.

Instead, Orff employs strong, simple, bold, sharply-accented rhythms; lots of repetition; and simple, major-chordal harmonic structures. If, back then, Stravinsky was writing classical music that owed a debt to jazz, perhaps Orff was writing classical music that would have owed a debt to rock… that is, if rock music had been invented. (Orff composed Carmina Burana between 1935 and 1936.)

As is the case with Also Sprach Zarathustra, the impact of the first movement or section relegates the rest of Carmina Burana to near-total obscurity. The whole thing is worth a listen though, at least once. Furthermore, in the recommended version, the vocal soloists are wonderful, especially Judith Blegen, as she scales the heights. Note, some of the poems are in Middle High German or Old French.

Just as I did last time with Also Sprach Zarathustra, here are three different recordings of the opening segment of Carmina Burana. That’s so that you can hear how different orchestras, choruses, conductors, and engineering teams have worked together to deliver the goods.

1. Michael Tilson Thomas, Cleveland Orchestra and Chorus (Columbia/Sony; recorded 1974).

It might seem strange to recommend a recording from 1974, given that hardly a year goes by without a new Carmina Burana recording that makes a splash. Please remember that my choice is personal. I do not claim that it is light-years ahead of all the competition. Find a version you like—Qobuz makes that easy.

The Michael Tilson Thomas / Cleveland Orchestra version was recorded during the time the LP-record industry was flirting with surround sound. Therefore, the (obviously, analog) master tapes were four-channel SQ Quadraphonic.

Even better, for the recording session, Tilson Thomas stood in the middle of the orchestra, which was arranged in a circle 360 degrees around him, to facilitate the Quadraphonic taping. While the stereo LP was very successful, the surround version was not a roaring success back then. However, today, the surround version can be heard, remastered on SACD.

My guess is that the CD reissue that is the source of Qobuz’ streaming content was a mixdown of the four-channel surround-sound tapes to stereo. That might account for the music’s clarity and power. Well, also: the Cleveland Orchestra is one of America’s top orchestras, and its chorus is top-notch too.

Furthermore, Tilson Thomas was at the start of his career, and he was eager to make a mark. That, he certainly did.

2. Krzysztof Penderecki, Krakow State Philharmonic Orchestra “Karol Szymanowski” and Chorus (Arts Music GmbH; recorded 1994).

Among people who care about 20th-century classical music, Krzysztof Penderecki’s is a household name… but, only as a composer. However, without question, Penderecki brings a refined musical intelligence to conducting the Carl Orff work that is a household name for nearly everybody else.

Penderecki’s interpretation, in terms of pacing and dynamics, rejects hyped-up excitement in favor of a serious, almost somber approach. After all, the message of “O Fortuna” essentially is, “Life doth suck; Therefore, everybody: Please weep with me!” Nicely-centered choral singing, too.

3. Herbert Kegel, Rundfunk Sinfonie-Orchester and Rundfunkchor Leipzig, and Dresdner Kapellknaben (Berlin Classics; recorded 1975).

Herbert Kegel conducts the Leipzig Radio Symphony with more of a sense of forward propulsion—and greater dynamic contrasts—than Penderecki. But while you or I might prefer one or another, I think they are equally valid.

In 1975, Leipzig was part of the Soviet bloc. But they certainly knew how to make excellent analog-tape recordings. (I’ve always said, good analog is better than bad digital—just as, good mono is better than bad stereo.) Somebody admired this performance enough to remaster it in 24/192 PCM digital. So, if a hi-res Carmina Burana is what you need, this is my recommendation.

Any discussion of “O Fortuna” must include the parody-lyric versions on YouTube [LINK], wherein people replace the Latin text with nonsensical English words. Another parody usage is the Carlton Draught beer television ad “It’s a Big Ad.”

(Editor’s Note: Mr. Marks is far too well-bred to note the most well-known use in low culture, namely the intro to Jackass: The Movie — jb)

I think the parallels in musical form between Orff’s “Neo Primitivism” and lots of rock music is why “O Fortuna” has latched onto the public imagination to the extent it has. Furthermore, in the case of the beer ad, I think that there are also parallels to the soundtracks of the Lord of the Rings movies.

4. Richard Hickox, BBC National Orchestra of Wales, II. “Red,” from A Colour Symphony, F. 108 (Arthur Bliss); (recorded 2006).

To follow Carmina Burana, here’s a rather different 20th-century musical expression of Medieval ideas: Arthur Bliss’ (1891 – 1975) A Colour Symphony. However, compared to Carmina Burana, A Colour Symphony might as well have spent the past several decades languishing in the Federal Witness Protection Program.

The famous English composer Edward Elgar invited the young Arthur Bliss to write a composition for a music festival to be held in 1922. Bliss decided to write a symphony, but he was a bit stuck for a theme—or even a mood. (“Composer’s Block,” rather than “Writer’s Block.”)

Browsing the bookshelves at a friend’s house, Bliss took down a book about Heraldry, which is the study of Coats of Arms and so forth. In reading about traditional heraldry’s associations of certain colors with various things or attributes (e.g., “Red—the colour of Rubies, Wine, Revelry, Furnaces, Courage and Magic”), Bliss found his inspiration.

There’s definitely something “cinematic” about Bliss’s style. My guess is that you could easily fool your music-loving friends into thinking that the movement “Red” from A Colour Symphony was an obscure forgotten score from the pen of film-music supremo John Williams. Indeed, Bliss wrote the film score for the UK’s first major-studio “talkie” science-fiction film, which was based upon H. G. Wells’ Things to Come.

Things to Come was released in the UK in 1936. Stanley Kubrick began working on the project that eventually became 2001: A Space Odyssey in 1964. That’s only 28 years. Science-fiction historian Gary Westfell called Things to Come “the first true masterpiece of science-fiction cinema.”

Westfall also stated that Things to Come was the “greatest ancestor” of 2001: A Space Odyssey. In fact, script co-author Arthur Clarke (whose 1951 short story “The Sentinel” was the source of the key plot device of 2001) insisted that Kubrick sit down and watch Things to Come, as an example of what a serious science-fiction film could be.

Hmmm. How about this? Could Bliss’s score for Things to Come have influenced Kubrick’s choice of “Sunrise” from Also Sprach Zarathustra for 2001: A Space Odyssey? One certainly has to wonder.

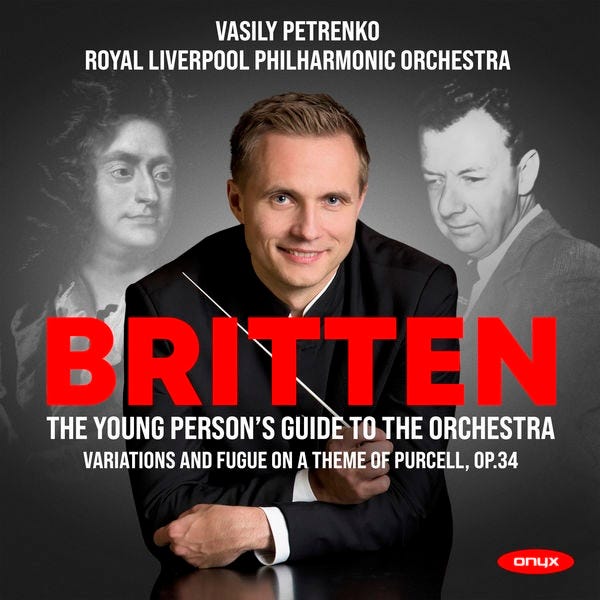

5. Vasily Petrenko, Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, VI. Fugue, from Variations and Fugue on a theme by Purcell (also known as The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra), Op. 34 (Benjamin Britten); (recorded 2017).

Literary critic Harold Bloom introduced the concept of “The Anxiety of Influence” in his book of the same name, in 1973. Bloom’s thesis is that because having a “voice” that is both original and authentic is so important to the poets of today, the idea that they might be influenced as much by the poets of the past as they are by their own muses creates anxiety for them.

I’ve never met Harold Bloom. But, if I were to; I’d say, “Hal, Buddy; that stuff you wrote about poets—that stuff goes more than double for composers.”

It took Johannes Brahms at least 14 years to complete his first symphony. Furthermore, depending on how you categorize several early sketches, that interval might really be as long as 21 years. Why? Because, as Brahms wrote to a friend, whenever he tried to write, he heard Beethoven’s footsteps behind him.

The “anxiety of influence,” indeed.

I have no idea whether Benjamin Britten (1913 – 1976) was anxious over the possibility that he had been influenced by Restoration-era Baroque composers such as Henry Purcell (1659 – 1695). But if he was, Britten came up with an elegant solution to that problem: showing off his own skills in composition and orchestration by writing variations and a fugue based on the Rondeau from Purcell’s incidental music to Aphra Behn’s 1676 play Abdelazer, or, The Moor’s Revenge.

Aphra Behn (1640 – 1689), by the way, was one of the first English women to earn a living by her writing. Also: Not that they had “James Bond Girls” in Restoration England; but, if they did, Aphra would have been one. Early on, Aphra worked in Antwerp as a spy for Charles II.

Benjamin Britten’s Variations and Fugue on a theme by Purcell is one of his most popular works. Deservedly so; its grandiosity never slops over into pomposity. And, in the same way as US jam-band Phish would open their live shows with “Sunrise” from Also Sprach Zarathustra; reportedly, veteran prog-rock-synth band Yes, starting in the early 2000s, would open their live shows with Variations and Fugue on a theme by Purcell. (Note, I heard Yes live, in 1972….)

6. Frederick Fennell, Cleveland Symphonic Winds, I. Chaconne, from Suite No. 1 for Military Band in E-Flat Major, Op. 28, No. 1, H. 105 (Gustav Holst); (recorded 1978).

If the name “Gustav Holst” rings a bell, it is because Holst’s most famous composition is the orchestral suite The Planets. “Gustav Holst” sounds like an echt-German name. Indeed, in order to be cleared to do volunteer work for England during World War I, Holst legally had to change his surname from “von Holst” to “Holst.”

Despite that, Holst the man himself was British through and through. His mother was of mostly English descent. On his father’s side, it was a mix of Swedish, Latvian, and German ancestry, although there had been successful musicians in the family in England for at least three generations. Holst was born in Gloucestershire, and studied at the Royal College of Music under Charles Villiers Stanford.

In his youth, Holst sometimes played gigs as a trombonist, in order to support himself. It must have been that experience that gave him such an intuitive grasp of wind-band orchestration. Holst’s Suite No. 1 revolutionized military band music, and it remains one of the most-performed pieces in that genre.

In 1978, before the (1982) advent of the CD, Frederic Fennell, often cited as the most important band conductor since John Phillip Sousa, made the first-ever digital symphonic-band recording, for LP release on Telarc. The later CD release was one of the “must-have” CDs for early adopters of the new medium; it remains fresh today. As far as I am concerned, there is no more-recent recording of Holst’s Suite No. 1 that has displaced this one.

7. Gianluca Cesana, from Clavier-Übung III, “Kyrie, Gott heiliger Geist,” BWV 671 (J. S. Bach); (recorded 2018).

There are so many well-played and well-recorded versions of the Bach organ prelude “Kyrie, Gott heiliger Geist” that it is difficult to pick just one. Gianluca Cesana’s excellent recording of a selection of Bach Preludes for the liturgical season of Pentecost differs from the usual pipe-organ recital, in that his solo-organ pieces alternate with a-cappella Bach choral works, beautifully sung by the Accademia Corale di Lecco.

The recorded sound is treasurable. The instrument is the 1978 Mascioni organ at the Church of Saint Alessandro in Barzio, Italy. With three keyboards and 38 stops, I would not call it a “monster” of an organ; but the sound is very rich and full. Listen for cleanly defined bass pitches from the pedals, and the overall harmonic “bloom.”

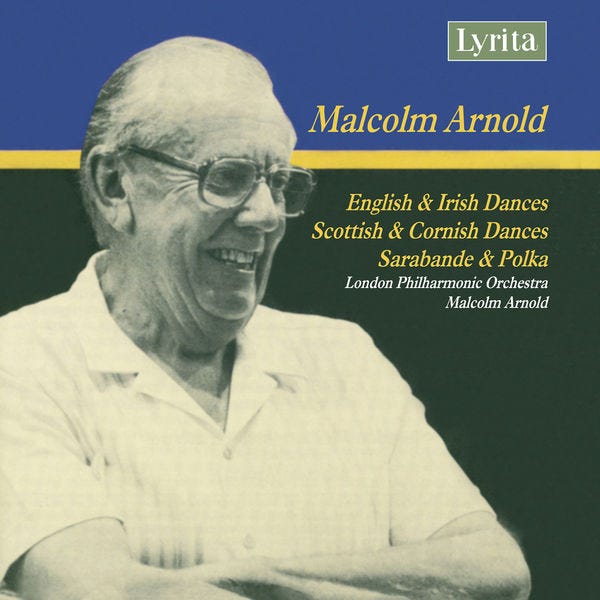

8. Malcolm Arnold (conductor), London Philharmonic Orchestra, from Four Cornish Dances, Op. 91: No. 3, Con moto e sempre senza parodia

(Malcolm Arnold); (recorded 1979).

Malcolm Arnold is not remembered that much today, especially among United States concert audiences. However, in mid-20th-century Britain, he was widely considered to be a composer of the same stature as Benjamin Britten and William Walton. Arnold was remarkably prolific. In the classical realm, he wrote nine symphonies, twenty concertos (including a clarinet concerto for Benny Goodman), and various other works.

Arnold also scored more than 100 films and documentaries, the most famous being The Bridge Over the River Kwai, which earned for Arnold an Academy Award (Oscar) in 1958, and a Grammy nomination in 1959.

For a 20th-century composer, Arnold’s style was evolutionary rather than revolutionary. He acknowledged being influenced by Berlioz, Mahler, Bartók, and jazz. Because his music was tonal, melodic, and, for lack of a better word, landscape-y, he was sometimes compared to Jean Sibelius.

Malcolm Arnold’s 1979 LP recording of his own British (English, Irish, Scottish, and Cornish) folk-dance orchestrations was heralded at the time for its remarkably realistic recorded sound. Even today, the digital version can stand with almost any “demonstration” recording, especially in this relatively recent (2019) 24/192 PCM transfer. At the end of Cornish Dance No. 3, the tambourine should appear to come from the far back of the soundstage.

The next installment will be the last. Its focus will be on “Pleasures, Both Innocent and Guilty.”

John Marks is a multidisciplinary generalist and a lifelong audio hobbyist. He was educated at Brown University and Vanderbilt Law School. He has worked as a music educator, recording engineer, classical-music record producer and label executive, and as a music and audio-equipment journalist. He was a columnist for The Absolute Sound, and also for Stereophile magazine. His consulting clients have included Steinway & Sons, the University of the South (Sewanee, TN), and Grace Design.

Thank you for highlighting Orff, whose music seems fallen out of his time, as if it were drawing from deeper, more ancient sources (a bit like Bruckner, though very different in style and effect). The carmina are rough and wonderful, definitely worth listening to the entire composition.

I listen to Holst's The Planets whenever I get a chance. I've always thought about seeking out his other works, and this has given me a good reason to do so. I will continue expanding my musical horizons. Thank you!