Guest Post: "Test Tracks #3", by John Marks

Free for all subscribers

(The story so far: Test Tracks #1 — Test Tracks #2)

Here are additional selections from the audio tracks I often use for the subjective evaluation of drivers and loudspeakers. The theme of this list is Diverse Music: Large-Scale Soundscapes (Part 1 of 2).

These tracks present unamplified music being played in a performance venue, rather than in a typical acoustically-dead recording studio. Moreover, as far as I know, with no added reverberation.

These tracks are available on Qobuz and Tidal playlists.

QOBUZ: https://play.qobuz.com/playlist/14651538

TIDAL: https://listen.tidal.com/playlist/7cc50a30-75ba-49a6-8ace-4e182d982767

Of course, for many of the albums these tracks come from, you can shop on eBay or on Discogs.com for the LPs or CDs.

Please note: To its credit, Qobuz does not “normalize” the volume level of its tracks; therefore, you might have to adjust the volume levels as you go. If you listen on Tidal, you might wish to adjust your Account’s Settings to defeat “Loudness Normalization.”

1 – 3. “Sunrise” (Einleitung) from Also Sprach Zarathustra (“Theme from 2001: A Space Odyssey”), Op. 30 (Richard Strauss).

The “short-short-short LONG” opening statement of the first movement of Ludwig van Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony is generally regarded as the single most recognizable theme or motto in Western classical music. By the way, when Musicologists speak of “Western” music, they are not talking about Cowboys and Indians. They are speaking of the music of the Western rump of the ancient Roman empire (meaning, Rome and its culture), as distinct from the Eastern rump of the ancient Roman empire (meaning, Constantinople and its culture). To put that in another context, the culture of Roman Catholicism, as distinct from the culture of Eastern (Byzantine) Orthodoxy.

That is important, at least to Musicologists, because when a composer of the past few hundred years sits down the write a “symphony,” the symphony’s formal structure, of discrete but inter-related parts (called “movements”), is based upon the multipart structure of the Roman Catholic Mass, and therefore of the music written for the Mass.

By the way, there’s a fascinating book on the “reception history” of Beethoven’s Fifth: Matthew Guerrieri’s The First Four Notes: Beethoven’s Fifth and the Human Imagination(2012).

A remarkable historical coincidence that only brought added luster to Beethoven’s masterpiece was the World-War-II-era realization that the Fifth Symphony’s “short-short-short LONG” motto was the Morse (telegraph) Code for the letter “V,” as in “V for Victory.” Thereupon, Beethoven was drafted into the antifascist cause. Which, I am sure, is where he would have wanted to be anyway.

(Editor’s Note: Beethoven couldn’t even decide if he agreed with Napoleon, waffling wildly on this at least twice — jb)

Beethoven’s Fifth is culturally important as all get-out.

But… I have never heard of a high-school or college marching band’s taking to the football field while playing the beginning of Beethoven’s Fifth(!). That honor belongs to Richard Strauss’ (1864 - 1949) musical treatment of Friedrich Nietzsche’s “philosophical novel” Also Sprach Zarathustra (“Thus Spake Zarathustra”), as featured in the opening of the film 2001: A Space Odyssey. “Zarathustra” being the German for Zoroaster, the Persian magus or prophet of antiquity.

Stanley Kubrick hired film-score composer Alex North to write an original score for his upcoming science-fiction film. That made perfect sense, because North’s score for Kubrick’s previous film Spartacus was a great part of that movie’s success. Furthermore, the Spartacus soundtrack LP album had been very successful. As was often the case, while North toiled away on his score, Kubrick chose “placeholder” music for temporary “guide track” synchronization with the film, as it progressed through filming and editing.

Fatefully, Kubrick chose “Sunrise,” the first section of Richard Strauss’ tone poem Also Sprach Zarathustra, as the placeholder music to accompany the interplanetary-sunrise “long shot” that starts the movie. After a brooding introduction of thrumming double basses underscored by a deep organ pedal, Strauss’ dramatically ascending three-note trumpet call (C – G – C8a) is answered by one of the punchiest two-note “responses” in Music History: the forte “dah-DAAAH!” of E descending half a step to E-flat, played as a “hairpin” (loud-soft-loud) by the full orchestra. Kubrick just could not bear to give up that impact!

So, when Alex North delivered his score, Kubrick politely ignored it. Kubrick also (somehow) neglected to inform North that he had decided to stick with his self-selected guide tracks. Adding insult to injury, North only learned about all of that by having to sit (awkwardly, is my guess) through the studio’s VIP pre-release screening in New York City.

My attitude is that if you cannot “name that tune” from those three ascending trumpet notes C – G – C8a, you have probably been living in a cave. Which, incidentally, is where Nietzsche’s fictional hero Zarathustra lived.

I have always wondered whether the fact that Strauss’ tone poem had its première in 1896 (and therefore, in 1968, at least in the United States, it likely was in the Public Domain, and therefore copyright-royalty-free), might have been in the back of Kubrick’s mind. But perhaps my 20 years as a trial lawyer somewhat soured me on humanity.

In parallel with the “Sunrise” saturation-bombing of popular culture from the late 1960s on—for examples, Elvis Presley’s live-show entrances; Eumir Deodato’s 1974 Grammy-winning jazz/disco/funk tribute; and jam-band Phish’s more than 250 live-show entrances—”Sunrise” became the favorite classical track of hi-fi salespeople across the land.

It’s a bit of a pity that the “Sunrise” performance on 2001’s actual film soundtrack, solely because of corporate agendas I won’t bore you with, is a “Frankentape.” Which means that the Vienna orchestra was recorded in a venue without a pipe organ. So, the pipe organ was recorded elsewhere, and then dubbed in. Ouch.

And then, once again, the result of inscrutable corporate agendas, while EMI was willing to license out Herbert von Karajan’s Vienna performance for the film itself (but, only as long as it was not identified in the closing credits), they weren’t willing to license it for the Original Soundtrack Album LP. Therefore, the 2001 (Un-)Original Soundtrack Album LP has Karl Böhm’s 1958 Berlin Philharmonic “Sunrise” recording, in place of von Karajan/Vienna.

There is a very readable book by a BBC journalist who decided to find out what this Zarathustra chap was all about: Paul Kriwaczek’s In Search of Zarathustra: The First Prophet and the Ideas that Changed the World (Knopf, 2003). Highly recommended.

I thought that it might be a wonderful Teaching Moment to present to you three high-quality, very well-recorded “ASV Sunrises,” so that you can hear how different orchestras, conductors, pipe organs, and engineering teams have worked together to deliver the goods.

In all of these, listen for the impact of the joined forces of string basses, pipe organ, and contrabassoon; the transient speed and clarity of the trumpet call; and the timbre of the full orchestra’s two-chord answer or response. Listen also for stereo soundstaging effects, and hall reverberation.

Two pointers: first, good headphones make for a great Reality Check.

Second, don’t let the contrast between the blockbuster blazing-sun “Sunrise” and the contrasting, smaller-scaled—almost intimate—following movement turn into a disappointment. The entire half-hour piece is worth a complete listen.

Over the course of that time, Strauss has a lot of orchestration tricks up his sleeve. Culminating in Also Sprach Zarathustra’s never finding or achieving resolution. Its end is a study in undecided incompleteness. The winds play in the key of B (five sharps), while the strings play in the paradoxically remote key of C (no sharps). And then, they all just fade away.

1. Andris Nelsons, Orchestra of the Leipzig Gewandhaus (Deutsche Gramophon; recorded 2022).

Andris Nelsons must have a gazillion Frequent Flyer miles. He is music director of the orchestras of Boston, USA, and Leipzig, Germany. I think that it is fair to say that Nelsons revitalized the Boston Symphony. Not long into his tenure, the BSO began racking up Grammys for Best Classical Performance and Best-Engineered Classical Performance. I had the privilege of watching Nelsons in Dress Rehearsal (for a concert performance of Richard Strauss’s opera Salomé, in fact), and I was hugely impressed by both his attention to detail, and his respectful collegiality with the orchestra members.

This Deutsche Gramophon recording is actually Nelsons’ third go-round on ASZ. Nelsons recorded it in 2012 (released on DVD or Blu-Ray only), with Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw orchestra. He also recorded it for CD release in 2013 or so, with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra.

So, we start here with the Leipzig Gewandhaus (the name means something like “Weavers’ Hall”), an orchestra whose history is inextricably intertwined with names such as Schubert, Schumann, Mendelssohn, Wagner, Brahms and Strauss. The earlier concert hall that first hosted the works of those musicians was bombed in 1944. The replacement hall was dedicated in 1981. Particular attention was paid to acoustics (which, sad to say, is not always the case…).

If it were not for the existence of Nelsons’ earlier ASV with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra; or the existence of Djong Victorin Yu’s Philharmonia Orchestra recording, this might have been my favorite-ever Also Sprach Zarathustra. There’s nothing at all to complain about! It’s just that the CBSO musicians seem to be ever so slightly more relaxed and confident in the music; the same for the Philharmonia. Furthermore, the pipe organs in the other two recordings are more gratifyingly prominent.

2. Andris Nelsons, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra (Orfeo; recorded 2013).

The Gramophone is the classical-music-recordings journal of record for the UK; and, indeed, much of the rest of the world. Every now and then, they update their coverage of standard-repertory pieces such as Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony; or, Also Sprach Zarathustra.

Not long after the release of Andris Nelsons’ City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra ASV, The Gramophone declared it to be the best ever. Or, if you prefer, the “GOAT.”

Now, of course, that does not mean that there is no other conductor with anything worthwhile to say! The Gramophone also singles out for praise: Serge Koussevitzky, Boston Symphony Orchestra (1935); Rudolph Kempe, Staatskapelle Dresden (1971); Herbert von Karajan, Berlin Philharmonic (1973); and Giuseppe Sinopoli, New York Philharmonic (1987).

3. Djong Victorin Yu, Philharmonia Orchestra (Guild GmbH; recorded 2000).

Now here’s a dark horse of a conductor—at least for USA audiences. Djong Victorin Yu was born in Korea, but he was educated at the University of Pennsylvania. Of his début recording with London’s Philharmonia Orchestra, Bill Newman wrote in CD Review, “His Mussorgsky Pictures reminds me of the young Karajan of the 1950’s . . . stunning. . . marvellous.”

It is often the case that I find it hard to put into words exactly why I prefer one particularly excellent recording over other, certainly excellent, recordings. I just love the “vibe” of this one.

But, if I had to give a reason (or a few), I think one reason would be that I get the feeling that Djong Yu is not at all interested in “being impressive” just for the sake of being impressive. Which, paradoxically, ends up being all the more impressive.

Djong Yu takes “Sunrise” about 20 seconds faster than Nelsons/CBSO. But, he never seems rushed. Also, Djong Yu manages to present the inner orchestral voices at the climax with a bit more clarity. A very big reason, of course, is Fairfield Halls’ Harrison & Harrison pipe organ (of 1964) with three manuals and 41 ranks of pipes.

If you really want to nerd out, in terms of critical listening: in the opening chord (pipe organ, string basses, contrabassoon, and tympani), the Berlin pipe organ and the CBSO recording’s pipe organ, at least to me, sound as though they are tuned slightly sharp of (or, higher than) the organ on the Philharmonia recording.

Pipe-organ sound is rather complex, so this is a matter not only of the pitch of the fundamental tone—the pitch of the name of the note. The “scaling” of the partials (or overtones or harmonics) of that pipe, which can differ slightly from organ builder to organ builder, will lead our ears in a particular direction. Also, the organ registration of “Sunrise’s” Pedal C most likely consists of a combination of 32-foot, 16-foot, and 8-foot pipe stops, some of which might come from different tonal families.

In other words, when the organist presses down the pedal for that single Low C note, three or more different pipes are sounding, each with its own overtone series and harmonic signature. (Also, quite a few pipe-organ builders reject the modern compromise of Equal (tuning) Temperament, with the result that there are different ways to divvy up the musical scale.) All of that is why the three organs in question all sound different, even though they are all playing the “same” note.

One can’t wrap up a discussion of ASV’s “Sunrise” without mentioning the 1970s recording by the World’s Worst Orchestra (the Portsmouth Sinfonia). This recording is obviously a spoof.

There are two stories out there. Story one, the group was formed by people who could not really play their instruments (mostly art students, in fact), so they just made noise for fun.

Story two: they actually could play, at least to some degree; but, to ensure a performance that was as far beyond “laughable” as the planet Jupiter is beyond the Moon, they swapped instruments. That means, the brass players were trying to hit High Cs on borrowed violins, while the violinists were trying to hit High Cs on borrowed trumpets. This is a recording that will last forever.

‘Tis pity the Portsmouth Sinfonia’s performance was not included on the Voyager Golden Records!!! That would surely make the Space Aliens think twice before visiting us!

4 – 5. Pierre Boulez, Vienna Philharmonic, “Trauermarsch” (Funeral March) and “Adagietto” from Symphony No. 5 (Mahler); (recorded 1996).

The recommended recording by composer and conductor Pierre Boulez might surprise, given Boulez’ own radical modernism as a composer. I think that what is going on is that Boulez wants the conductors of his music to pay attention to the instructions in his scores. Therefore, Boulez does everything he can to treat Mahler the way he himself would like to be treated. Not incidentally, the large concert hall in Vienna is considered by acoustical experts to be one of the top three concert halls in the world.

Sorry if you did not get the memo, but: “Mahler Is the New Beethoven.” See, e.g., Why Mahler?, Norman Lebrecht (Anchor Books, New York, 2011). To the music!

Gustav Mahler (1860 - 1911) and Richard Strauss shared a long-lasting but guarded friendship. After all, they were professional competitors both as conductors and as composers. Furthermore, Mahler was a bit put off by Strauss’ opportunistic careerism, while Strauss looked down upon Mahler’s working-class Jewish origins. (Mahler’s paternal grandmother had been a peddler with a pushcart.)

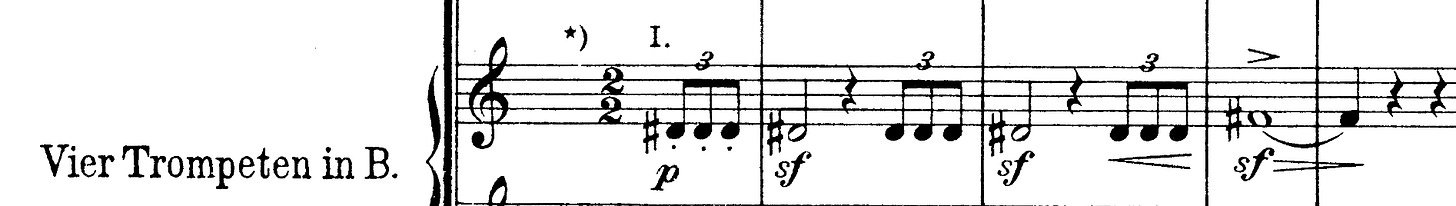

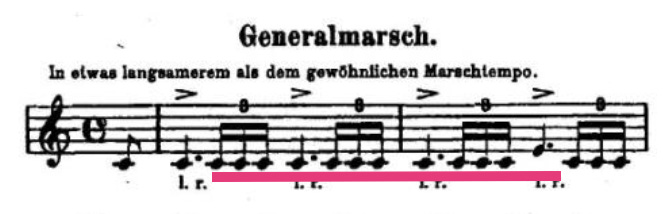

Nonetheless, one has to wonder whether the orchestration of the opening of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony (composed 1901 - 02), wherein a solo trumpet blasts out what sounds like a re-worked version of the “short-short-short LONG” opening statement of the first movement of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, might also owe something to the trumpet solo in the “Sunrise” opening of Strauss’ Also Sprach Zarathustra. Here’s a grab from Mahler’s score:

Strauss’ Also Sprach Zarathustra had its première in 1896. Mahler’s Fifth Symphony was first performed in 1904. Therefore, Mahler likely had heard ASZ live; or, at least he had had a chance to examine the score.

Mahler could have opened his Fifth Symphony in any number of ways. I think it is certainly possible that the idea of getting peoples’ attention with a blazing trumpet call just might have come from Strauss’ Also Sprach Zarathustra, which was fresh in peoples’ minds. (Note, the opening of Beethoven’s Fifth is scored for clarinets, bassoons, and orchestral strings—so there is no trumpet in that mix.)

Once the specific orchestration idea of a trumpet call was in mind, Mahler does seem to have borrowed the musical shape of his Fifth Symphony’s opening trumpet call from the “Presentation (or Inspection) March” of the Austro-Hungarian Army.

The fact that an Austro-Hungarian Army march sounds like a cousin to the opening of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony just might be a coincidence. Or, perhaps not.

In a sense, Mahler grew up with military music. The story goes that when Mahler was a child, the brass band of a military detachment in his home town would often parade through the center of town. Little Gustav would trot along behind, playing his toy accordion. (If that doesn’t humanize Mahler, nothing will.)

From a modern perspective, Mahler might appear to be a bit obsessed with death. However, the all-important context is that eight of Mahler’s siblings died in childhood. By the time he was a young adult, Mahler was well-acquainted with grief that was personal and intense. One of Mahler’s early song cycles is entitled Kindertotenlieder, which translates as “Songs Upon the Deaths of Children.”

Here’s my advice: When you ask a girl you are very much smitten with to attend a symphony concert with you on St. Valentine’s Day, first check the orchestra’s program. If the featured work is Kindertotenlieder, find somewhere else to go. (Epic fail.)

Bottom line, it is no surprise that the first movement of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony is called “Funeral March.” The first movement is full of colliding themes and abrupt dynamic contrasts, to the point of chaos. This is Mahler’s depiction of a tormented struggle against darkness and nothingness.

Relief comes in the fourth movement (Adagio), scored for orchestral strings only, accompanied by harp. No question, this love-letter of a movement is a poignant testament to the power of love. Gustav Mahler and Alma Schindler soon married…

However, Gustav foolishly squelched Alma’s ambition to write music of her own. Then, their daughter Maria died, aged four. Later on, to a certain degree, Gustav emotionally abandoned Alma, in his desperate determination to compose all the music he possibly could, before his (predicted) early death. Alma, in turn, famously cheated on him. (You can look that up. Tom Lehrer wrote a famous comedy song about it.)

As the Roman poet Virgil wrote, circa the year 19 BCE:

Rerum lacrimae sunt.

“These are the tears of things.”

Or, “These are the things that make you cry.”

John Marks is a multidisciplinary generalist and a lifelong audio hobbyist. He was educated at Brown University and Vanderbilt Law School. He has worked as a music educator, recording engineer, classical-music record producer and label executive, and as a music and audio-equipment journalist. He was a columnist for The Absolute Sound, and also for Stereophile magazine. His consulting clients have included Steinway & Sons, the University of the South (Sewanee, TN), and Grace Design.

I sampled a bit of the Idagio app last year, but I didn't end up keeping it past the trial running out because I just don't have the knowledge of classical music to justify it every month. But if this is a regular feature I may have to rethink that. Fantastic article, thank you.

Wonderful. Thank you for not only the selection but the education. Learning more about the selections in the previous posts has been great and will enjoy listening to these as well.