Weekend Music: One Of These Two Albums Is Not Really A Seventies Reissue

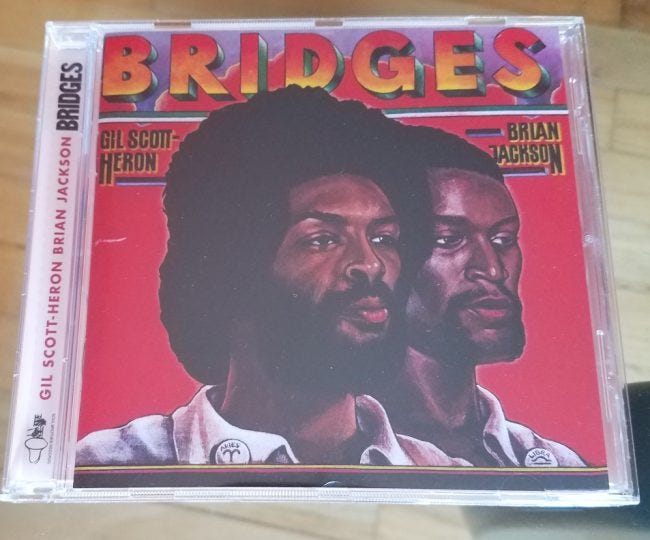

Long-time TTAC readers might be aware of my affection for Gil Scott-Heron and his early work with keyboardist Brian Jackson. Their album Winter In America is one of the all-time greats, written and recorded without a single misstep to convey a message at once deeply nostalgic and radically political. His talent was so incomprehensibly massive that it swallowed him whole, turned him into a self-destructive crackhead who ended up dying of AIDS just as the hipsters had taken notice of his swan-song album, I'm New Here.

Progressive white America never really took to "GSH". I suspect it was because your "woke" types get off on feeling superior to the objects of their putative compassion and admiration. It's no great trick to feel superior to Drake or Tyga or Kendrick Lamar; they're drooling morons babbling into a microphone, the African-American equivalent of Nikki Sixx or Justin Bieber. Artists like John Coltrane and Miles Davis might have been major talents but their primary allegiances were to the church and/or the female body, which made them safe and comfortable for a white audience. Scott-Heron, by contrast, was a nightmare fusion of Promethean IQ and keen insight, delivering lyrics with a pace and panache somewhere between laconic and surgical, unflinchingly focused on politics and race in a manner that couldn't be bought off with a Bentley or a promise of reparations. You'd need a pretty stout sense of self-image to feel equal to the man, much less superior to him. It doesn't help that he never really saw anything wrong with his cocaine use or his voracious sexuality; our modern progressive catechism demands that you either do penance for your perversions or take a defiant, self-conscious pride in them. Scott-Heron didn't apologize for his life and he didn't demand that we have a special month for crackheads. He simply liked drugs and he respected your right to not like them.

No surprise, therefore, that not all of Scott-Heron's work has proven easy to find in the modern era. In particular, his "Bridges" album, recorded with Jackson in 1977, never got anything besides a small-scale vinyl release courtesy of Arista. Is that because, or despite, of the fact that it contains the haunting track "We Almost Lost Detroit", which refers to the 1966 partial meltdown of a breeder reactor? Regardless, the album is now available courtesy of UK-based Soul Brothers Records, which cleaned up the original master and turned it into a spacious, musical CD.

Each one of these tracks could make a career for someone else, but Scott-Heron and Jackson carelessly piled them atop each other like Scrooge McDuck tossing stacks of money into the fireplace. The only song that fails to charm is "Tuskeegee #626", but it serves as a bit of a palate cleanser in the middle of the action and it's a useful reminder of a time when "institutionalized racism" meant something more serious than a shortage of brown faces in luxury-car advertising. (Find out more about the Tuskegee Experiment here.) "Racetrack In France" manages that trick of simultaneously brimming with enthusiasm and bitterness. "Delta Man" is an unvarnished masterpiece that will stay engraved in your mind after a single listen.

You can find all of the Bridges songs on YouTube and Vimeo. Scott-Heron is dead and his family is embroiled in legal turmoil over the estate, so there's no reason to feel bad about hearing the music at no cost. Yet I think it's worth buying the album for the purpose of supporting the Soul Brothers label and their tireless work in restoring previously unavailable music.

Speaking of previously unavailable...

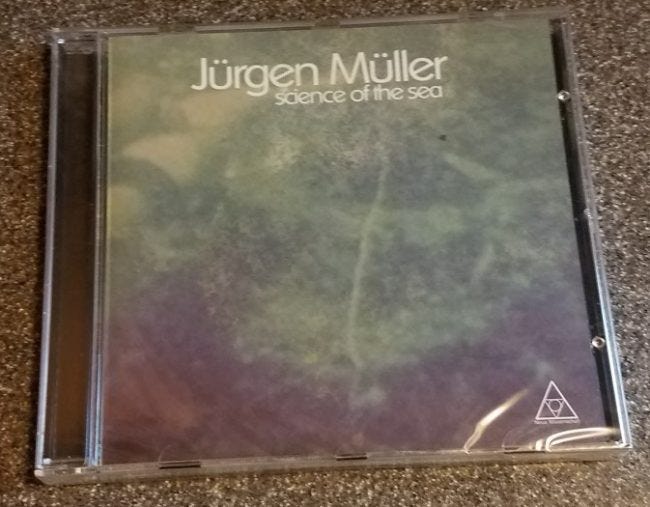

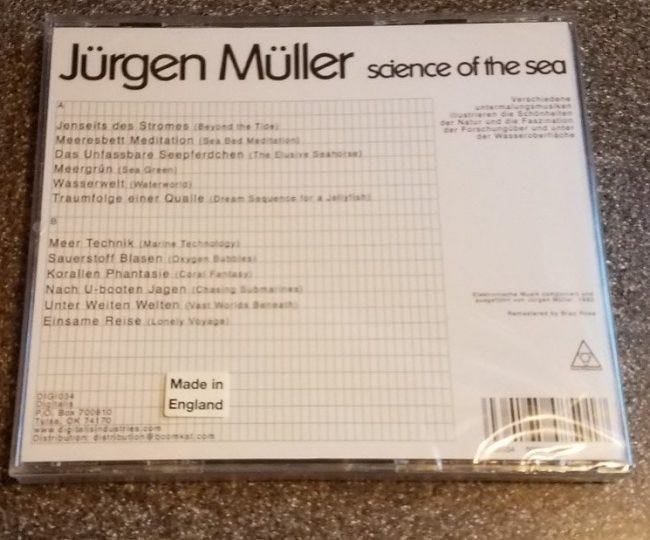

Back in the late seventies, self-taught amateur musician and Oceanic science student at the University of Kiel Jürgen Müller, set up a mobile studio in his houseboat whilst docked outside Heikendorf on the North Sea. Upon joining a film crew accompanying a mission to document sea-water toxicity testing he found himself captivated by the sea more on an artistic than scientific level and decided to document it himself through music, created with his own and other borrowed electronic instruments. After recording several reels of music and with the intention of becoming a composer for documentary film, he set up his own publishing company, Neue Wissenschaft, but due to studies and other commitments it wasn’t until 1981 that the first sessions began. They weren’t completed until a year later, at which point the majority of the subsequently pressed one-hundred copies were sent to friends and family with few ever reaching potential clients. Müller subsequently abandoned his musical aspirations to purse oceanographic science.

Sounds hard to believe --- and it should, because it's not true. Pitchfork expressed doubts at the time, but still gave it Best New Reissue upon its re-release. Which was really just a release. Jurgen Muller never existed and "Science Of The Sea" was recorded just a few years ago by a fellow named Norm Chambers, also known as Panabrite. Precisely thirty-six minutes long, this eerily soothing album consists largely of arpeggios over slow background chord changes. I'm currently listening to music via a rather exotic signal chain of Sony ES SACD player -> Bricasti M12 -> Bricasti M15 -> Magnepan 1.6 and on that hardware Science Of The Sea absolutely shimmers. Perhaps the most comforting part of it is the light frosting of white noise laid over everything to support the backstory of this being a thirty-six-year-old analog recording.

I won't commit a Pitchfork-ian error by claiming that I can absolutely distinguish the presence of analog synths on this album --- but it's my experience that a true analog synth, one that generates its music through oscillators, simply sounds more "real" than a digital emulation of the same. The move to digital chip-synths is one of the reasons, in my opinion at least, that Eighties and early-Nineties recordings don't "hold up" the way their Seventies counterparts did. The God-dammed Yamaha DX7 did more to destroy music than any other single instrument in history. Enough about that. With Science Of The Sea, Panabrite has created a brilliant album that, for me at least, has already proven to be tremendous background music for writing and editing. That sounds like faint praise but it isn't; your subconscious rebels against bad music in a manner that your conscious mind often deliberately suppresses. I'll be picking up the rest of the Panabrite back catalogue in the near future.

Thanks for reading --- and if you want better-educated rants about music, don't forget to check out my friend John Marks at his blog, The Tannhauser Gate.