The Story Of Zola

To be authentically middle-class is to forever live in a prison of one's own making. It means trying to make good choices in school and trying to marry the person you're supposed to marry and trying to live in a manner that would bear intimate inspection by another authentic middle-class person at any moment. It means delaying gratification and avoiding passion, paddling desperately to keep up with the financial and totemic accomplishments of one's peers while at the same time never flying too high above the flock.

We inmates of the middle class envy the rich for obvious reasons but we also envy the poor, because they have freedom. Case in point: the eternally brilliant song "Tangled Up In Blue".

Readers who are familiar with my views on authenticity in music won't be surprised at my admiration for "Tangled". It's the perfect distillation of freedom and its discontents, of people who are truly itinerant, meeting from time to time in a manner that seems directed by Fate because there's certainly no middle-class ambition or guilt directing the steps that each of them take. Imagine being a married man mowing a suburban lawn and considering some of the lyrics:

We drove that car as far as we could Abandoned it out West...

I had a job in the great north woods Working as a cook for a spell But I never did like it all that much And one day the ax just fell So I drifted down to New Orleans...

I seen a lot of women But she never escaped my mind

And then you have the masterstroke verse:

She was workin’ in a topless place And I stopped in for a beer I just kept lookin’ at the side of her face In the spotlight so clear And later on as the crowd thinned out I’s just about to do the same She was standing there in back of my chair Said to me, “Don’t I know your name?” I muttered somethin’ underneath my breath She studied the lines on my face

If you tell me how you personally react to that paragraph, I'll know almost everything I need to know about your upbringing. For me, it's thrilling and terrifying all at once. The unselfconscious way in which our protagonist and the object of his desire swim in that dirty sea, the lowbrow world of sex work and itinerant existence and apathy and alcohol use. They aren't playing at being "those people" the way that kids from good schools do when they go to the Cheetah on a Friday night or to Vegas for a weekend. They aren't constrained by guilt or expectation; they don't even feel the weight of such things on their shoulders, because nobody ever bothered to lay it there.

Yet it took a nice Jewish boy like Bobby Z, an inmate of the middle class himself, to draw that picture for us. The people who really live like that don't bother to write or sing about it. They simply exist. It's no big deal to the hero of "Tangled" that his woman is stripping, the same way the narrator of the Grateful Dead's "Operator" blithely tells us

She could be hangin' 'round the steel mill, Working in a house of blue lights. Riding a getaway bus out of Portland, talking to the night. I don't know where she's going, I don't care where she's been, Long as she's been doin' it right.

Every middle-class kid who ever heard those lyrics shivered a bit. My woman could be anywhere. She could even be turning tricks. She could literally be getting plowed by a bunch of mill workers RIGHT NOW. But my love for her is strong enough to let that go. What a delicious thing to contemplate for people brought up on the idea that at any moment one unforgivable thing, like failing to graduate with honors or permitting the grass behind the house to grow above the acceptable height, could be cause for permanent banishment from society.

Compare the blithe assurance of the fellow on the phone in "Operator" with the central character in John Cheever's The Swimmer, who finds himself estranged from reality itself by a career mistake. To be in the middle class is to perennially be under threat. But to be the main character of a Dylan or Grateful Dead song is to be poorer, and lower, and free.

It's not necessarily a criminal world, or an outlaw one. It's merely one where the gravity of expectation pulls at a Martian, or perhaps a lunar, level. It means that you can spend a weekend on a pontoon boat or a summer working casual labor in Mississippi. You can get in the car without any fixed idea of the arrival time at your destination; indeed, without a fixed idea of the destination itself. Most enticingly, it's a world where nobody brays at you about your potential or your talent or your gifts. To be among the untouchables is to have no potential worth noticing and therefore to be free from the necessity of servicing that potential.

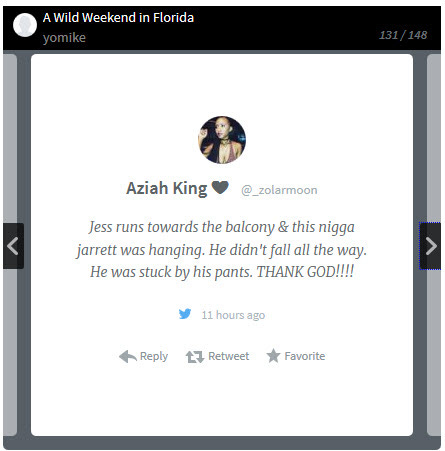

The advent of "social media", which is to say, media created by and for the proles, has given all of us frustrated middle-classers additional insight into how the other half lives. The most fascinating thing right now on "Black Twitter" is the story of Zola. From the moment the narrator starts talking about "hoeism", you know it's going to be good --- but it becomes absolutely epic. It's an Elmore Leonard novel mashed-up with a Robert Beck story and a Rihanna beat.

If you start reading the Storify I bet you finish it. The reason is simple: you won't be able to believe that these people are getting away with it. Any one of the various misdeeds described by Zola would be enough to destroy a middle-class life, but these people take it all in stride! They're operated purely by their emotions of the instant. Alliances form and disintegrate. Zola "fucks her man quiet" so she can go on a stripping trip. At one point, one woman forces another woman to perform oral sex on her fiance so the situation can calm down.

Is it real? I have no idea. It feels authentic because it is so senseless. Any middle-class person who cooked the thing up would give it more narrative drive and less prole-ish screwing around. But the thing about poor people is that they are not narrative driven. They are moment-driven. It's their curse and their blessing. It's why one of my best friends, who has millions of dollars in the bank, stays awake all night after a minor market adjustment yet I used to watch people in the county jail sleep like children up until the very moment they were pulled out for their murder trial.

Most interestingly of all, because it's not a Dylan song, the fact that some of the people involved in the story are sex workers does affect their relationships. Just not like you'd expect, unless you, too, grew up beneath the underdog. So here's to you, Zola: may you remain tangled up in the green stuff.

“Don’t talk about it, Tom. I’ve tried it, and it don’t work; it don’t work, Tom. It ain’t for me; I ain’t used to it. The widder’s good to me, and friendly; but I can’t stand them ways. She makes me get up just at the same time every morning; she makes me wash, they comb me all to thunder; she won’t let me sleep in the woodshed; I got to wear them blamed clothes that just smothers me, Tom; they don’t seem to any air git through ’em, somehow; and they’re so rotten nice that I can’t set down, nor lay down, nor roll around anywher’s; I hain’t slid on a cellar-door for—well, it ’pears to be years; I got to go to church and sweat and sweat—I hate them ornery sermons! I can’t ketch a fly in there, I can’t chaw. I got to wear shoes all Sunday. The widder eats by a bell; she goes to bed by a bell; she gits up by a bell—everything’s so awful reg’lar a body can’t stand it.”

"I seen a lot of women But she never escaped my mind" ~ this still bothers me thirty years later .

Yes, "Operator" like "Cat's In The Cradle" and many other what I call "White Man's Blues" .

"is to be poorer, and lower, and free." ~ No, Jack 'poor' is a state of mine that has nothing to do with money .

-Nate