The Sorrow Of Philippe Wynne

"I guess the hardest part to take was being there and knowing that both of your parents were still alive."

“He could hold the crowd spellbound… by himself, just his voice.” My former business partner, the Jim Brown lookalike and Range Rover 4.6 Vitesse enthusiast “Uncle Ron”, had a special place in his heart for a second-tier Seventies R&B group called the Spinners, and for lead singer Philippe Wynne in particular. Maybe “second-tier” is unkind. The group had six Top 40 hits between 1972 and 1980, and several #1 hits on the Billboard R&B chart. Certainly I knew at least a slice of their music in my youth; until he reached his sixties and settled down into his current playlist of “talk radio played at two decibels over ambient” my father was a stalwart devotee of R&B and was far more likely to have the radio in his LeSabre or Town Car tuned to a “black” station than to a “white” one.

Still, the Spinners weren’t quite on the same level as Al Green, the Temptations, or any of the R&B acts with full-bore crossover success around that time. Like Parliament or Clarence Carter or Johnny “Guitar” Watson, the Spinners lived on the far side of the color line, selling and performing to primarily black audiences. I’m guessing most ACF readers won’t know them at all, beyond perhaps a dim recollection of “Then Came You”, performed with Diana Ross:

I never knew love before / Then came you / Then came youuuu

Uncle Ron used to hand out home-burned CDs with what he felt with the Spinners highlights, to which he would affix laser-printed labels of his own design. “THE BIG DOG BARKS BACK… SPINNERS GREATEST HITS”, in block font over a generic night skyline. His mastery of digital audio wasn’t quite up to his affection for stock clip art; all the songs were boiled down from Red Book CDs to early 128Kbps MP3s then bounced back up to 44.1Khz for audio CD duty. At the time, I put the abysmal quality of the discs down to “old R&B shit”, but that was unfair. Most of the Spinners records were done in workmanlike if not spectacular fashion in everyday Detroit studios to standards that were well below “Steely Dan” but also not Springsteen’s “Nebraska”.

Thankfully, Spotify and Qobuz both have the full catalog in good condition, so you can hear these tunes in better repair than I originally did. Uncle Ron was right: Philiipe Wynne was a one-of-a-kind talent and with a tragic backstory that seems to live right in the heart of the black American experience.

Born in Cincinnati during WWII, Wynne and his three siblings were abandoned by their mother, who ran off to Detroit to be with some other dude. Their father was a traveling laborer who couldn’t keep an eye on them, so when Wynne was ten years old he and his siblings were placed in an orphanage. In an interview decades later, he would say "I guess the hardest part to take was being there and knowing that both of your parents were still alive."

A few years later, he ran away from the orphanage to find his mother in Detroit. Once established there, he performed with a variety of musical groups including the JBs. In 1972 he replaced his cousin as the lead singer of The Detroit Spinners, an R&B group that had toiled in the Motown system for more than a decade. Motown was famous for “using the whole animal”, so to speak, with their artists, so the Spinners were reportedly pressed into being drivers and roadies for more successful groups.

In 1973 the Spinners left Motown and recorded The Spinners for Atlantic with producer Thom Bell, also known for his work with the Stylistics and Delfonics. Think of The Spinners as the group’s version of Appetite For Destruction; it was a fully-formed and adult release that permanently defined their sound to the market in a way that would be hard to follow up.

Mighty Love, however, was no Use Your Illusion. Released six months or so after The Spinners, it was if anything “more black” and “more Philly” than its predecessor. Both albums went gold, meaning the band could support a major-venue tour.

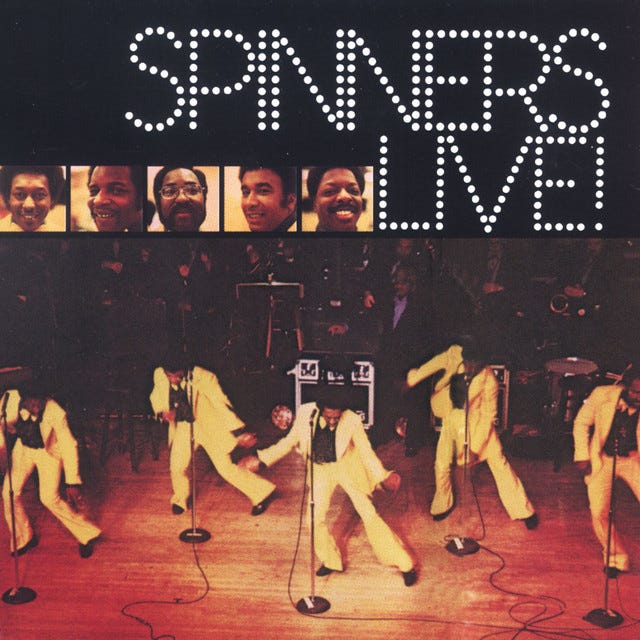

Listening to Live! by the Spinners tells you so much about Seventies R&B. To begin with, the band is absolutely dead-tight, channeling and expanding the backing tracks developed by Philly house band MFSB. As a pure vocal group, the Spinners are free to sing their hearts, which they do, Wynne in particular.

For a long time, I’ve been personally fascinated by the difference between — and I’m simplifying here, please forgive me — black live music and white live music. In the latter, the audience is subservient to the performer. You didn’t go to a Beatles show or Boston concert thinking you were anything but a faceless crowd member who would passively receive whatever the band wanted you to hear. The band would always start late, they might not do encores, they’d make you listen to their new album that flopped or creaking prototype songs in the process of being developed. If the band included Axl Rose or Perry Farrell, they might not start at all.

(Miles Davis, turning his back on the audience, probably did the whitest thing in the history of performance; it perfectly encapsulated the idea of musician as superior to listener.)

Black groups didn’t do that — especially not if they learned their trade in the “chitlin circuit” or similar small-club tours. Years ago, I had the pleasure of watching “soul blues” player Theodis Ealey, whose biggest hit instructs listeners that some vaginas are so big you need to stand up in them if you’re going to make an impression, play Yoshi’s in Oakland. He had a raggy-ass Godin LGX-SA guitar with broken knobs and a hundred-foot cord, at which my purist mind gagged — and he used it to walk around the club, talking to people, involving them in the music. Much of the Yoshi’s crowd was flabbergasted; they’d come to hear

THE BLUES

not

THE SOUL BLUES

and there’s a big difference. THE BLUES is a dead art form thoughtfully reanimated in respectful fashion by professionals who perform Robert Johnson tunes with “maximum authenticity” to all-white audiences. THE SOUL BLUES has “Ms. Jody”, who sings tunes like “Your Dog’s ‘Bout To Kill My Cat” and “Still Strokin” to all-black audiences in Quonset huts around the South. Those audiences expect to be entertained, and they have no concept of a professional distance between them and the musicians.

Watching the tech-zillionaire, ultra-hip Yoshi’s crowd put their heads in their hands while Ealey sang

But when you add his time up / He was just a five minute brother /He used to lick it

was one of the great joys of my life, I have to tell you. Eventually, Ealey settled down and played a couple traditional blues tunes without the Casio-synth backing that was also horrifying the purists, at which point everyone appeared to be satisfied. But he clearly thinks of himself as an entertainer in a way that, say, Thom Yorke or Bono never could.

Similarly, the Spinners are entertainers and they actually devoted a portion of their 1974 concert recording to… cover tunes. A medley of cover tunes, actually, in which they impersonate various people from Al Green to… Elvis and Tom Jones! In fact, about half of the cover tunes are of white artists. Can you imagine some modern no-talent like Common or Cardi B taking time out in the middle of a concert to cover white tunes? But the audience — which, based on everything I can determine, has fewer white people in it than the average Red Lobster — adores it. It’s a big-hearted crowd that has no interest in hating anyone.

The album ends with an eight-minute version of “Mighty Love”, capped with a long vocal solo by Wynne and a longer play-out in which the band is recognized. It’s an outrageous indulgence so I had to check: the original release of Spinners Live! was a double album, folded into a 67 minute CD. So yeah, it was on the record players that way in 1975.

I defy anyone to hear the whole album and not be astounded by Philippe Wynne’s voice, which is truly unique and evocative. It’s hard to imagine that anyone else could do what he does. Unfortunately, Wynne felt the same way. Already in his thirties, he recognized that he’d never make “fuck-you money” as one-fifth of the Spinners. First he tried to have the group renamed “Philippe Wynne and the Spinners”, but was unsuccessful. In 1977 he left and recorded a solo album, Starting All Over, with Steve Gadd and other all-stars as a backing band. Oddly enough, much of the music is written by Alan Thicke, who was also the dude who gave Wynne the idea to strike out on his own.

It’s not a great record, and Thicke’s idea was not a good one. The follow-up was recorded with George Clinton, and I can’t find it anywhere. Apparently it sank like the proverbial stone. It took Wynne two more years to get enough capital and goodwill together to make a third solo record; this one’s worse yet and it comes across to modern ears as the worst of dime-store soul-blues Casio-keyboard trash.

The Spinners, meanwhile, had a couple of Number One hits on the R&B charts with recycled Fifties songs. (It’s embarrassing to recall, but much of Seventies culture was actually Boomer nostalgia for the postwar era of their childhood.) The obvious thing to do was to get the band back together and move strong into the Jodeci / Babyface era of R&B with some “grown folks music”. A few sources indicate that such a thing was contemplated, and Wynne sat in with the Spinners for a few shows, but he died before anything could happen in the studio. On stage, in a small club, just singing and working to pay his bills, at the age of forty-three.

There’s one track on Spinners Live! that deserves particular attention. It’s “Sadie”, and it tells the story of a young mother with nine children who sacrifices herself to make sure they make it to church and keep food in their bellies. Wynne sells it so hard, so emotionally, that I always thought it was about him. “You see,” he tells the audience, in a voice halfway between song and sob, “there was nine of us.” The tune had a massive impact on Black audiences, to the point where it was covered by both R. Kelly and 2Pac Shakur (as “Dear Mama”). Listening to it, you can just imagine a young Philippe Wynne trudging to Sunday School while his mama cleans the floor at home.

It’s a lie, of course. The song was co-written by three music-industry veterans. Wynne was an orphan of convenience, abandoned because his real mother wanted to suck some other dude off besides his dad, and badly enough to leave the state over it to boot. Yet in that moment, on the live album, when he cries “I love you Mama,” you can hear every single yearning he ever had for just that kind of mother, just that kind of life. A thirty-two-year-old man without a family, brought to minor fame late and with just a decade of struggle and uncertainty ahead of him before an untimely death. Was it heartfelt, or simply the purest art possible?

Doesn’t matter. Ron was right. Philippe Wynne could hold the crowd spellbound, just his voice. He can do it today, fifty years after the record and thirty after his death. In the last couple of days, I’ve had conversations with two of my favorite automotive writers. They’re both stuck with an outlet that does very little traffic and gets little respect in or out of the industry. And they’re under the thumb of a deeply damaged and insecure momma’s boy who can’t tell the difference between genuine affection and a parody of it paid for with someone else’s cash — or perhaps doesn’t want to know the difference.

I told them both this: If you want to be a writer, as opposed to an executive who writes or a businessman who writes, all that really matters is the craft and what you produce. It can outlast you. Not forever, and not universally. But it can last. So you have to focus on that and let the rest roll off your back. If you write something genuinely worthwhile, genuinely memorable, that speaks for itself. Whether it is seen by seven people or seven billion people. If you would be a writer, then write.

Today I’ll give “Sadie” another listen. Out of genuine affection, and respect. For a man who lived his whole life in sorrow and yet managed to create art from it, art that no managed to lift other people’s spirits even if his own were beyond rescue. It’s worth remembering if you are trying to create something durable in a miserable situation. Sometimes that’s how you do it. How you have to do it. Or, to earthily quote a character in LeGuin’s The Dispossessed: “Grain grows best in shit.”

The best "Philly Sound" band came from Detroit. Fight me. Rubberband Man is arguably the most infectious song ever recorded.

Come for the spicy insider accounts of the automotive industry, stay for some cultural enlightenment.