The Power Of The Teddy Bear

As a child, I was fascinated by machines; as an adult, I am increasingly obsessed by the operation of the human mind. Note that I don't say "the human brain", although that's interesting as well. But that's the hardware end, if you will. It's the mind, the software, that I'd like to understand. Humanity, to our knowledge, is utterly unique in the possession of consciousness. Which is in and of itself a problem. How do we know we are conscious?

Much of my thinking on consciousness is the product of two very different books. About twenty years ago, I first read Douglas Hofstadter's Godel, Escher, Bach and I've been turning the ideas expressed in that 777-page monster around in my head ever since. GEB is sort of a shotgun dissertation about consciousness and identity in which the author attempts to formulate a mathematical basis for the uniquity of the human brain. It's not an easy read, even for brilliant people, and there's a lot of pages that look suspiciously like a college math or comp-sci textbook in it. Many years later, the author wrote I Am A Strange Loop to present the same ideas in an easier-to-access format.

My one-paragraph distillation of GEB is that any system of sufficient complexity might develop the ability to observe itself. Insert "SkyNet" joke here. The book features an ant colony as one of its "characters". Although none of the ants possesses individual consciousness, the ant colony as a whole is capable of thinking, communicating, and acting as a conscious being. It sounds ridiculous until you consider that: hey, an individual brain cell isn't conscious, a small cube of neurons isn't conscious, a dog isn't conscious. At some point there's a threshold that is crossed and consciousness arises. (If you're wondering about whales, which have much larger brains than we do, perhaps the problem for them is the structure of their glia. Or perhaps they are brilliant thinkers who have no way to let us know.)

The appeal of Hofstadter's theory, as laid out in his books, is that it would be possible to build true artificial intelligence by simply building a computer of sufficient complexity and an appropriate software load. But it's by no means proven, and some of the most brilliant humans alive have expressed sharply different opinions. Roger Penrose, as an example, believes consciousness to be a quantum mechanism, and his opinions are difficult to refute.

On the other hand, we have Steve Grand's Growing Up With Lucy, which takes a completely different approach. Grand argues that intelligence and consciousness are the products of input, not capacity. In other words, you could have creatures that are much less complex than a human being --- but if they had to solve the same problems that humans do, they might "evolve" consciousness. In other words, a massive brain locked in a box with no external inputs would never become conscious, and the eventual consciousness of any brain is largely a product of its external environment.

One of the most terrifying parts of Grand's book is the part where he discusses the vast disparity between reality and human perception. What we see as "reality" is in fact a waking dream constructed by your brain based on what it's absorbed as inputs recently and what it believes the future will be. The brain itself, due to the relative slowness of the human neural network, is always "living" about a quarter-second behind reality. But since living in the past leads to falling off rocks and being eaten by tigers, there's a surprising amount of processing that's done outside the brain. Driving a race car at the limit, for example, involves very little conscious thought and a lot of learned reactions being processed no further than the brain stem. The same is true for running or throwing a ball or...

wait for it...

...engaging in a fast-paced argument or conversation.

Grand argues that in a very real way, we don't usually know what we are going to say until we say it. That the deed is father to the word, not the other way around. That our intelligence is closely tied to language, because the brain is often incapable of thinking about things without talking them through.

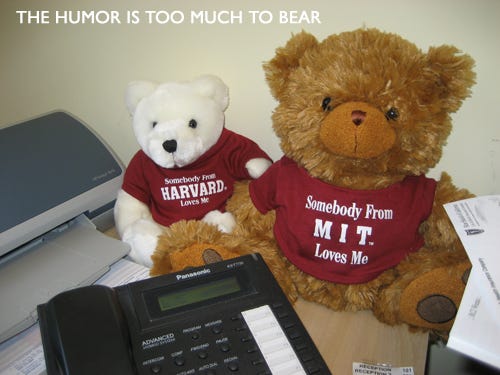

Which leads me to the MIT Teddy Bear, as described here

Ahh there's a nice trick I learned for this. I think it's something they used to do in tutorials at MIT but I never got around to trying it at UNSW. It's the classic thing you start explainging your problem to somone and then half way through it's like don;t worry I worked it out.

MIT's solution to the problem was the following. Every computer Lab had a teddy bear sitting in one corner (substitue with penguins/daemons) where apropriate. If you were a student in the class and had a problem you had to go an explain it verbally to the teddy bear first, only then could you ask the tutor :)

I've used this philosophy again and again ever since reading about it a long time ago. When I was a sysadmin at (INSERT MAJOR COMPANY HERE) I'd ask people to explain things to the whiteboard before they asked me for help. The whiteboard saved me a lot of hassle and time, which I then used to send combative text messages to the women I loved. It was fascinating to watch people literally talk themselves into the answer. The simple-minded explanation for that was: they always knew the answer deep inside. The scary, more true explanation: the answer didn't exist until they started talking.

The human brain is a flawed system and it is not terribly compatible with real time or real life. Which makes me think that, if there is a heaven, it won't be a place above the clouds where you can race at LeMans or jam with Page and Mozart. It will consist of transferring our consciousness, our self-aware program, into the universal mind of God. That we will have access to knowledge on an atomic level. That we will be freed from our plasma prisons and experience a plane of consciousness far above our monkeyish existence. But once we know everything, will we be content?