The Persisting Significance of the String Quartet

All subscribers welcome!

QOBUZ PLAYLIST https://play.qobuz.com/playlist/21792259

My favorite Political-Science Question-and-Answer Joke goes like this:

Q.: What is the difference between Perception and Reality?

A.: Reality, you can change.

Among the various musical genres, I believe that Classical String-Quartet music is perceived to be the musical equivalent of Spinach (or perhaps Broccoli). Yeah, sure, eating Spinach is unquestionably “good for you.” But… lots of chewing is called for, and the flavor experience can be a bit tepid.

I also think that there is a perception that music for string quartet is the ultimate effete, classist, “holding your teacup with your pinkie finger lifted” music. Most “normal” people might think that opera is classist; but I think that opinions on string-quartet music are even more negative.

However, the reality is a lot more complex, and a lot more interesting.

My “Exhibit ‘A’ for the Defense” is this very jazzy string-quartet movement that Maurice Ravel composed in 1903:

My thesis is that music written for the ensemble of two violins, one viola, and one cello constitutes the musical art form that most nearly approaches perfection, both in its past achievements and its present possibilities. The greatest minds and most perceptive dispositions find in the literature and performance of string-quartet music an endlessly self-renewing source of wonder and delight. The string quartet is a most felicitous meeting of potential and realization.

Why should this be so? I offer four reasons for the past and continuing significance of the string quartet.

First, the string quartet is one of the few Western musical ensembles that can play reliably in tune across all the musical keys. Historically, even from the time of Pythagoras, issues involving pitch, intonation, scales, tunings, and temperaments have together constituted the single most daunting technical problem in music. The development of the string quartet allowed composers for the first time to create harmonic tension by letting the music explore remote keys without sounding out of tune.

Second, a string quartet is capable of performing music at the outer limit of the complexity that even a trained listener can comprehend, at least in one pass. Orchestras are, by definition, larger; but, in terms of the essential nature of the music and its inherent level of complexity, orchestration is often just a matter of the composer’s wanting different tone-colors, dynamics, or sound effects than a string quartet can provide. Writing for an orchestra is rarely a matter of expressing complexity beyond the capability of a string quartet.

Third, for the level of complexity desired, a string quartet consists of the irreducible minimum of players, with no need for outside control by a conductor. The instruments of a string quartet cover the range from high female voice to low male voice, while providing opportunities for harmony and counterpoint limited only by the composer’s imagination and the players’ skills. There is, of course, a creative tension between the medium’s possibilities for individual expression, and the necessity for a unified and cogent approach to the music. That tension is certainly part of the art-form’s fascination.

Fourth, although it is my argument that the symphonic masterworks of the era from Beethoven to Mahler would have been impossible but for the musical foundation of the string quartet from Haydn through Mozart and on to Beethoven, the continuing significance of the string quartet lies not only in carrying on a venerable tradition, but also in the medium’s accessibility and openness to fresh ideas, and new means of expressing them.

The string quartet provides a composer of today with an outlet for creating music that is more likely to be heard than is a symphonic work. Symphony orchestras are expensive to run, and symphony-orchestra programming, especially in the United States, tends to stick to the tried-and-true recognized masterworks, or crowd-pleasing showpieces.

Given the number of string-quartet ensembles out there, the number of programs they play each year, and, dare I say it, the perhaps more informed and/or adventurous approach to music that string-quartet fans exhibit in contrast to symphony fans, a contemporary composer with a new string quartet is more likely to have it widely performed, and perhaps even recorded, than if he or she were to write a symphony.

This practical consideration is apart from and in addition to the essential virtues of the quartet medium, among which are clarity, concision, tonal beauty, and an often higher level of technical attainment. You don’t hear flubbed French-horn entrances in a string quartet.

To recapitulate so far: the form of the string quartet solves the problem of out-of-tune remote keys, allows for as much complexity in musical utterance as most composers have desired, has a perfect ratio of labor to management, and has been and remains an incubator for musical progress.

Although the instruments of the violin family achieved their essential form about 1550, and the period from 1660 to 1780 is generally regarded as the golden age of violin making, the string quartet as we know it did not arrive until created by Franz Josef Haydn, around 1750.

Between 1550 and 1750 the members of the violin family were used primarily in larger groups: in opera, instrumental, and church music. The violin of course had a strong tradition of solo concerto performance, and to a lesser extent so did the cello, but before 1750, chamber-music ensembles almost always included a keyboard instrument, and usually a wind.

The typical Baroque trio-sonata ensemble would consist of a string instrument, usually a violin, and a wind instrument, such as flute or oboe, and a continuo (today we would say rhythm) section consisting of either a cello or a bass, and a keyboard. So, yes, a Baroque trio-sonata composition, so-called for its three-line structure, was actually played by four instruments. And yes, you can bet that that will appear on the final exam. <Grin>

That 200 years passed between the full development of the instruments of the violin family and the flowering of the string-quartet form can only be explained by the supposition that even as early as 1550, composers were so acclimated to writing in ways that avoided the tuning problems inherent in having strings, winds, and keyboards play together, that it took both genius and circumstance for the expressive possibilities of a more evenly-balanced ensemble, and one not hampered by intonation difficulties, to be realized.

To explain that assertion more fully: The Baroque trio sonata developed during the first flowering of relatively sophisticated composed music for domestic enjoyment. In most cases, the continuo parts (both keyboard and bass), could be played by amateurs of modest gifts, and with a minimum of preparation. In this regard I want to remind you that Charles, the for-the-moment “Cosplay King of England,” was an amateur cellist. In many cases, one or both of the Baroque trio-sonata leading voices also could be played by amateurs.

Circa 1550, professional music performance was limited to the theatrical stage and the church; concert halls did not yet exist. Before the 1580s, most sheet music was written out by hand. But, in the 1580s, plate engraving began being used for music scores, which revolutionized the business of music in the same way that moveable-type printing had revolutionized the business of literature.

Because most of the customers for keyboard and chamber-music sheet music (who were usually also the at-home performers), wanted galant, frothy, and most of all playable music, there was no pressure on composers to push the envelope, either in terms of technique, or content.

When Haydn was court composer for the Esterhazy family, he was in essence marooned in the outback of Hungary. There, he had the time, the inclination, and the players of professional quality to bring the string quartet to the level of development where we see it today:

• a medium for the expression,

• by professionals of the highest caliber,

• of a composer’s most profound thoughts and emotions.

Haydn let go of the prevailing frothy, galant, and entertainingly lightweight style, and brought a new sense of urgency and drama to musical language, in large part by tonal and harmonic daring.

Haydn outlived his chief patron at Esterhas, and the younger generation put Haydn out to pasture. Pasture turned out to be Vienna, where the daringly dramatic tonal rhetoric of Haydn’s later quartets had a decisive influence on a young man who perhaps otherwise would have turned out to be nothing more than a successful Viennese society pianist: Beethoven.

Beethoven’s quartets and symphonies cross-pollinated each other, with the result being that Western music was forever changed. Western music was liberated from the need to rely upon words to express specific meanings. The specific meaning that Beethoven conveyed in his music is the transcendent worth of the individual. That is why all the technical stuff matters.

“Does anyone have an ‘A’”?

I doubt that space considerations will allow me to do justice to the physiological, physical, and acoustical matters that conspire to create the problem of tuning and temperaments.

Doubly unfortunately, a limited discussion does not allow an adequate grounding in the basics, with the result that there is an unavoidable element of circularity in terms and definitions.

Musical tones have a quality known as pitch. For two given notes of different pitches, one will sound “higher” to people than does the other. Pitch is expressed as frequency of vibration. The more vibrations per second, the higher the perceived pitch. Vibrations are expressed in cycles per second, called Hertz in honor of a German physicist.

Most physical objects vibrate in complex ways. Most objects vibrate at a fundamental frequency, while simultaneously vibrating, though with lesser energy, at integer multiples of that frequency. These multiples are called harmonics.

If two tones have frequencies that are in a ratio of 2:3, such as A 440Hz and E 660Hz, it is conventional to say that they span the interval of a “fifth.” This is potentially misleading, for two reasons. First, it is not a question of one thing’s being one-fifth of something else, as is the case with a bottle of vodka’s being one-fifth of a gallon. This figure of speech only means that in a conventional Western scale, when you start with A and include it in the counting, E is the fifth note.

The second pitfall is that to call E the fifth note implies that there are only three notes between A and E, whereas there are at least 6: B flat, B, C, C sharp, D, and D sharp. If you use intervals smaller than a half-step, which is again a circular definition, you can have, in practical terms, as many microtonal note pitches as you care to provide for.

Beyond this, the conventional Western scale with eight tones, the last being twice the frequency of the first, therefore called, in true circular fashion, the octave (rather than the “double”), carries within it a tonal ambiguity.

Octaves are harmonically easy. They are always in tune because the harmonic vibrations of the lower note encompass and duplicate the fundamental and harmonics of the higher note. So-called fifths are easy also, because the odd-order harmonics of the higher note correspond to the even-order harmonics of the lower note. The intervals of thirds and sixths are secure in pitch also, although less so than fifths.

Now, let’s suppose we were to limit the notes a musical instrument could play to a key note, the third, the fourth, the fifth, and the seventh intervals (and also the octave of the first note, to complete the scale). One such pentatonic (five tone, as opposed to octave/eight note) scale would consist of the the notes d' e' g' a' b' d'. Whereas, each set of five black keys on a piano makes up a G-flat (or equivalently, an F-sharp) major pentatonic scale.

In such scales, every note you could play on that instrument would harmonize acceptably well with every other note. That is because the harmonics would either match up closely enough, or miss by far enough, that there would not be dissonant beating, or sour derived tones. The pentatonic scale is the usual scale for most non-Western music. Also, in today’s Early Childhood Music Education, there are special Pentatonic recorders (the wind instrument) and harps. So that the wrong notes are less jarring.

Since ancient Greek times, though, Western scales have sought to have it both ways: wanting the greater melodic and harmonic possibilities inherent in having more notes in the range within octaves, yet seeking to avoid out-of-tune harmonies.

For those of you with some music-theory background, I want to emphasize that the harmonic ambiguity of the octave scale scheme is not limited to those cases when modulating from one key to another results in the accidentals (sharps or flats), being off in the remote key. Even if you stay only in one key, there is a harmonic problem in the octave scale.

This is because in building a scale, and the usual choice for theoretical discussion is the scale with keynote C, the choice of whether you locate the second pitch by intervallic reference to the fifth or the sixth will give you different results. That is the famous Problem of the Two “D”s, or the Syntonic Comma. To note another facet of the same problem, you get a different pitch for D depending on whether you go up melodically from C, or down harmonically from A.

Those of you without some music-theory training will probably just have to take it on faith that filling out the pentatonic scale with the extra notes of the second and seventh pitches, which did add melodic possibilities, opened up a Pandora’s Jar of harmonic difficulties. Which are only multiplied when changing keys. The purportedly same note of B-flat sounds differently whether it is played harmonically correctly in the keys of F or D-flat.

Human voices can solve the syntonic-comma problem by adjusting the pitch of a problematic note with reference to what came before, or by what the harmony is. Organs and other keyboards, however, are fixed in pitch, and that is where the intractable problems arose.

As an aside, Medieval theoreticians called the interval of an augmented fourth, which they called the “tritone” (because they did not include the bottom note in counting), Diabolus in Musicum (“the Devil in Music”), on account of the likelihood that a harmony would be sour. Later on, Bach’s organ writing tended to avoid the third intervals that were likely to sound iffy on the German organs of his time.

Things only got worse when players, especially of organs and other keyboard instruments such as harpsichord, tried playing outside of the safe major keys of C, G, D, and A. A scale built harmonically from scratch in a remote key such as D-sharp will have accidentals that sound differently than the same notes in a scale built harmonically from scratch on A.

This is in part because of the logarithmic nature of scales: the octave from lowest piano A to the next one up spans a range of 27.5 Hz; the next octave spans a range of 55 Hz, the next one 110, and so on, with the top piano octave spanning 1,760 Hz. Changing the key note changes where the fractional intervals fall.

Most keyboard students know at least the first page of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier (of 1722), which was written (in part) as advocacy for a novel tuning scheme that sought to play in tune in all keys. Today’s keyboards use a compromise “Equal Temperament” scheme in which all the notes are theoretically off perfect pitch by the same amount, regardless of the key played in.

(Earlier attempts to work around the tuning problem included keyboards with “split” divided black keys, wherein, for example pressing down the left side of one particular split black key would sound a justly-intoned D-sharp, while pressing down on the right side would sound a justly-intoned E-flat.)

When you consider that many early wind instruments had difficulty getting any sound out at all while trying to play notes outside of their home keys, it is little surprise that music written for amateur use in the eighteenth century was no more tonally or harmonically adventurous than the rock-and-roll of the 1950s. Ah, Peggy Sue.

On most bowed string instruments, pitches are found by precisely placing the player’s fingers on the strings. Unlike on a guitar, there are no frets to establish fixed intervals (the bowed-instrument exception being the antique Viola da Gamba). The only fixed pitches on a bowed string instrument are its open strings.

In the unlikely event that an open string’s natural pitch would turn out to be harmonically problematic in a given key, all notes except the lowest string’s open pitch can be sounded, with appropriate pitch refinement, by playing stopped or fingered notes on the immediately lower string.

It is precisely this tonal and harmonic flexibility that Haydn, and those who followed him, seized upon, in opening music’s horizons to the range of light and shadow of harmonically distant keys. And I am afraid that that is all the time we can spend on theoretical matters.

On to the music.

Note, I do not so much “rank” these compositions by greatness, or order them chronologically, as list them by my subjective judgment as to their “Accessibility.” The most accessible composition for string quartet (IMHO) is Ravel’s, as shown in the first video. Please also note, that for any given recommended work, the YouTube video embedded here, and the complete performance on the QOBUZ playlist might be different.

Antonín Dvořák wrote his Quartet No. 12 as a love letter to America. He had spent one of the few untroubled times of his adult life vacationing in a Czech community in Spillville, Iowa. He was in America both teaching and conducting.

The quartet opens with the kind of open-hearted, plain-spoken utterance Dvořák had come to value from Americans, and continues from happy inspiration to happy inspiration. One of which is the call of the songbird that announced the dawn for Dvořák, who wanted to sleep. I use the term plain-spoken advisedly, as both melodically and harmonically Dvořák largely stayed with pentatonic intervals.

Most of you are familiar with the reality of the Doppler effect, even if you may not know what it is called. Doppler was the first to account for, as a matter of theoretical physics, the experience of a sound source’s seeming to change in pitch as it travels toward and then away from an observer. First higher, and then Dopplering lower, as we say, the prime example being the lonesome sound a passing railroad train makes. In the last movement of the Dvořák, listen for the harmonically daring double-stopped phrases Dopplering down, as Dvořák bids farewell to America.

Beethoven wrote 15 string quartets, which are usually grouped into Early, Middle, and Late periods. Beethoven’s Late string quartets are generally regarded as among his most challenging works, and I do agree that that holds true for his final efforts in the genre. However, Beethoven’s Op. 127 has one of Beethoven’s loveliest slow movements. Not hard to get into at all!

With Claude Debussy’s String Quartet of 1893, we come full circle. The problems of pitch, tuning, and temperament that the Medievals, Bach, and Haydn wrestled with, can also be dealt with by embracing them.

The musical culture of Indonesia is based on a pentatonic scale, the prime apparent virtue of which is harmonic coherence. While the West tried one compromise scheme after another to avoid dissonance in an octave scale, the Indonesians, who theoretically had the problem licked, crafted their instruments with built-in harmonic differences.

The chime-gong instruments of the Gamelan orchestra are forged and tuned in pairs, each slightly off pitch, so that when the pairs are played together, a shimmering curtain of dissonant harmonics is created. Western music derives much of its motoric force from the tension of traveling through harmonically remote keys. Indonesian music derives much of its motoric force from the played notes’ pointillistically approximating unplayed but pure consonant tones.

At the Paris Exhibition in 1889, Claude Debussy heard a visiting Javanese Gamelan orchestra. That experience revolutionized his harmonic thinking, and gave birth to musical Impressionism. Debussy’s achievement is that, while writing in the Western idiom for Western instruments, he was able to express the Balinese ideal of a serenely floating encounter with another world.

And again, for those of you with some musical background, I do want to point out that what Debussy heard was an Angklung Gamelan, the refined music of the royal court. The much more dynamic, even frenetic, Gamelan Gong Kebyar, which is what most people who have heard some Gamelan music have heard, is an invention of the early 20th century, and is at home in the villages.

The string quartet had its beginnings in 18th-century aristocratic patronage. Today, it remains one of the most challenging and rewarding of all musical forms. Dedicating the leisure time of one’s life to keeping current with its unfolding, I assure you, will be time well spent.

For Further Listening

If you don’t happen to have a QOBUZ subscription: first of all, they offer a 30-day home trial. If that does not work for you, it should be rather easy to just do YouTube searches for these works, which are not meant to constitute an historical survey. These are my choices for “Accessibility.”

To take one example of an exclusion that some might question, Shostakovich’s 15 string quartets are among the most important musical works of the 20th century. But, at the moment, I cannot think of one of those quartets that does not sound as though it was written in Stalin’s shadow, and with Shostakovich in fear of being sent to the Gulag—or worse. (Which his quartets, of course, were.)

Maurice Ravel, in F (1903)

Antonín Dvořák, No. 12 (1893)

Claude Debussy, in G, (1893)

Samuel Barber, in B minor (1935-1943)

Ludwig van Beethoven, Op. 127 (1825)

Joseph Haydn, No. 30 in E♭ major, "The Joke" (1781)

W.A. Mozart, No. 18 in A Major, (dedicated to Haydn) (1785)

Franz Schubert, No. 14 in D minor, “Death and the Maiden” (1824)

J.S. Bach, The Art Of the Fugue, BWV 1080 - Version for String Quartet

Edward Elgar, in E minor (1919)

Jean Sibelius, Op. 56, “Voces Intimae” (1909)

Alfred Schnittke, No. 3 (1983)

Peteris Vasks, No. 2, “The Songs of Summer” (1984)

Olivier Messiaen, Quartet for the End of Time (1941)

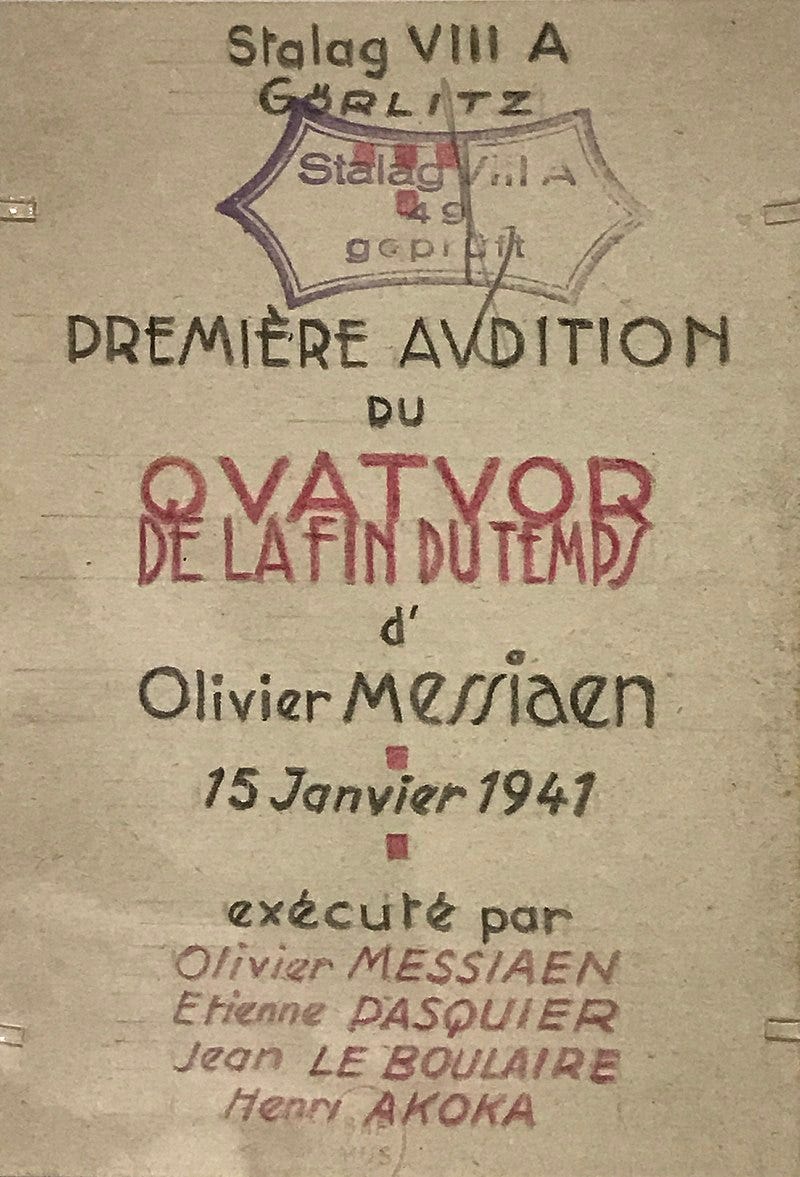

Of course, Messiaen’s famous Quartet is NOT a string quartet; it is an eight-movement chamber-music suite for the unusual combination of piano, clarinet, violin, and cello. Sorry, I could not resist. I think that familiarity with the Quartet for the End of Time is an absolute necessity for Literacy in 20th-century culture.

I also cannot think of a piece of music with a more compelling Origin Story. Olivier Messiaen was taken prisoner by the Nazis during their invasion of France. He was sent to a Prisoner of War camp in what is now Zgorzelec, Poland. A sympathetic prison guard gave Messiaen a small pencil and some paper. (Please ponder that for a bit.)

Even though he was freezing, and also so hungry that he was having auditory hallucinations, Messiaen composed a musical monument of great spiritual depth. Quartet for the End of Time’s première was in the Prisoner of War camp on January 15, 1941.

Messiaen, a devout Catholic, dedicated his Quartet “To the Angel who announces the End of Time.” That’s because Messiaen’s inspiration was from the Book of Revelation:

And the angel which I saw stand upon the sea and upon the earth lifted up his hand to heaven, and sware by Him that liveth for ever and ever... that there should be time no longer… .

Perhaps some of you will not be surprised to learn that the principal extrinsic musical influence upon Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time was Balinese Gamelan music, the same as Debussy’s (String) Quartet.

Well, I don’t want to end on such an emotionally-heavy note, so I will leave you with this:

In my career as a classical-music record producer, my most successful projects were the series of “String-Quartet Christmas” recordings by Arturo Delmoni and Friends. After the implosion of my boutique micro label, my friends at Steinway & Sons bought the master tapes and reissued all three CDs as a boxed set. Steinway makes that boxed set available for free streaming (though not at CD quality) HERE.

My personal opinion is that Volume Two/CD Two (tracks 25 through 46 in the Steinway stream) has the best combination of, interesting music choices—a few of them quite unfamiliar; a high level of instrumental playing; and hign quality recorded sound. So, I have added those tracks to the QOBUZ playlist.

I'm a violinist who could have ended up as a professional orchestral musician with a couple of different decisions in my 20s. Why orchestral instead of chamber music? Because a major symphony job pays the bills, or at least did in the days before we decided that, in the name of the neighborhood character, only the PMC should be able to afford places to live. It is very easy to form a quartet as a side project and very hard to make any money at all with it.

I feel more or less the same way that you do, but I think the quartet is a bit of a compromise for practicality. You can't get certain textures with it that you can with a couple more instruments. But violinists are a dime a dozen, while violists and cellists are rarer, and four players are easier to find and schedule than more players.

My very favorite chamber ensemble is the string sextet with two violas and two cellos. Unfortunately, there are relatively few works for the format. But Tchaikovsky's "Souvenir de Florence" shows why I love it. So many different textures, so much more richness than he could have achieved scoring the same music for a quartet. Brahms also wrote two of them, the first of which is a spare and simple thing of beauty. Schoenberg's "Verklaerte Nacht" doesn't get any respect because it was still tonal and Romantic in nature, but I find it one of the most moving pieces of pure programmatic music in the literature, and he makes dazzling use of the textures the sextet form makes available. Dvorak wrote one too, although it's not among his best works. There are a bunch of practice pieces from Boccherini and minor works from Rimsky-Korsakov and Dohnanyi. In short, it's a format that a contemporary composer could write for and have a legitimate shot at becoming part of the canon.

Turning back to the quartet, while you have listed a bunch of accessible examples, I feel a duty to cite the most difficult one. Beethoven originally wrote his "Grosse Fuge" as a final movement of the Op. 130 quartet, but everyone hated it, and he had to write a more conventional final movement in order to get the quartet published. He then published the Grosse Fuge as a standalone work. It's the most harmonically and contrapuntally unconventional thing he ever wrote. It makes no effort to be either pretty or accessible. It aims for complexity and difficulty as goals in themselves. But if you get past the intimidating and sometimes ugly surface, you start to hear 250 years into the future. Beethoven anticipated everything from Webern to heavy metal to hip-hop in one piece that he wrote when he was deaf, sick, and going crazy. The Alban Berg Quartett (in general, one of the best quartets ever to do it) released a version in 1987 that is appropriately unrestrained and unconcerned with niceties, and you will learn more from it on the 150th listen than on the first.

A week ago we had tractor comparison tests. Earlier in the week we had another entry in a series of essays about kittens. Now an exposition on the importance of string quartets to musical theory with a short history lesson on how they came to be. All on a substack that is nominally about cars, motorcycles, and auto racing. You gotta love this place.