The Midwit Killer

In which I demonstrate my ability to have predicted the future, then predict it again

Didn’t I just kinda-sorta write about ChatGPT a month ago? I did — but hold onto your hats, because I also wrote about it just over three years ago, when it did not yet exist. In that article, which discusses its predecessor GPT-2, I predicted that

At some point, someone is gonna have the bright idea to let the successors of GPT-2 start doing real work. Most of the time, it will go pretty well. You could use GPT-2 to answer customer service emails, schedule appointments, determine more efficient routings for freight and packages and whatnot. The more success these programs have, the more chances they will get to succeed.

Naturally, I did nothing at all to take advantage of this entirely correct prediction, such as going to work for a GPT vendor or developer, because

a) I’m a complete idiot when I’m not being a remarkable genius; and

b) I had a dream job overseeing some of my favorite writers and people, said job being one from which I was going to retire.

In the three years and twenty days since I made that prediction, and most notably in the past 180 days, GPT has gone from “nerd curiosity” to “midwit obsession.” It’s kind of the Macarena for people with 110-130 IQs; they don’t understand where it came from or why it’s doing what it’s doing, but they know they need to get on board. This has of course led to all sorts of unintentionally hilarious behavior on the part of people who don’t understand computers or creativity.

The nice people at The Intercooler decided to pit Dan Prosser against ChatGPT in a battle to write a story about Enzo Ferrari. It was obvious to me immediately that the deck was stacked in favor of the computer here, because

a) writing a biography of someone who has been dead for a long time, and about whom millions of publicly-accessible words have already been written, is a dream date for ChatGPT, because the program primarily works by emulating what it’s read; and

b) the human involved was Dan Prosser.

This isn’t Jesse Owens vs. a horse; it’s more like finding a homeless person outside your $4M San Francisco walk-up and having him race a horse. Nothing against Dan, who has written some enjoyable stuff — but he’s not exactly a titan of persuasive prose, or even the best of the trash-bird hardcover-book automotive-history regurgitators. Against him, even a program that one of my correspondents recently called “Autofill Deluxe Platinum” in an Instagram message stands a fair chance.

(Mostly unrelated note: my friend Colin Comer has a great new book about Shelby American, available here. If you read that book in conjunction with Preston Lerner’s thoughtful and human-oriented Shelby American volume, I think you’d learn every single thing that is worth learning about the man, the company, the cars, and the era. I just wish these two good dudes would get together and write about a company of the current day that interests me, such as Radical Performance Engines, or RealDoll.)

That phrase — Autofill Deluxe Platinum — is both an utterly brilliant way to explain how ChatGPT works and an example of authentic human creativity at its very sarcastic best. We’ve all used autofill, voluntarily or not, in our email programs. I find that it is very good at doing one-line responses to the sorts of communication I get from job recruiters, people looking to set an appointment, or my child’s mother. (Who is a very smart woman and probably recognizes it every time.) The main difference between autofill programs and ChatGPT is processing time plus, if various trolling experiments can be believed, about ten thousand programmatic rules to ensure social justice at all costs.

To people who don’t understand computers, ChatGPT has the appearance of genuine intelligence — but to people who don’t understand physics, the bowling ball test is certain death. Let’s not ever let stupid, or merely uneducated, people dictate how we look at things. The difference at the moment, of course, is that we don’t have a hundred million middle-class people panicking about what a cable-mounted bowling ball is going to do to their careers.

Consider, if you will, Brian Scotto’s post above. Don’t dismiss it just because it is riddled with grammar and meaning errors. Scotto is very much a somebody in automotive media, having single-handedly elevated Ken Block from “normal business dude who probably made $100,000,000 by having shoes sewn in sweatshops, some of which got caught using child and prisoner labor, and along the way making dead sure that USA skate shoe manufacturing was permanently destroyed” to “RADDEST MOST EXTREME RACING DRIVER OF ALL TIME” via a series of Everyman-oriented “Gymkhana” videos.

Scotto’s assertion that “it will learn to be more creative than us” is absolutely false and always will be. But why is it false? To understand that, we need to spend a few minutes talking about tough stuff. If any of it is unclear, that’s my fault. Ask your questions in the comments, which are open to all subscribers, and I’ll do my best to clarify.

Creativity has many facets but it boils down to two steps: ideation and winnowing. Don’t bother to Google (or ChatGPT!) that; it’s my phrasing. In ideation, we come up with ideas. In winnowing, we remove bad ideas, or remove the bad parts from a good idea.

There is some evidence to suggest that in human beings, both of these are quantum phenomena. The idea comes to your head unbidden, and you immediately know if it is any good. A couple nights ago, I couldn’t sleep so I sat down and wrote a song based on a vocal line that came into my head. I didn’t think of a hundred lines; I thought of one. But it is believed by some thoughtful people that what I experienced was a quantum collapse of possibilities. There were many songs in my subconscious that “collapsed” into one when I started humming.

An easier-to-understand version of this: You see a car coming towards you on the highway. For a while, it could be any car. Then you narrow it down a bit. Then it resolves into a particular car. You make a subconscious decision. And at that point, you start to “see” details that you didn’t see before, based on your decision. When I was a child, all the GM C-body and B-body cars had very similar noses. Sometimes I would think I was looking at a 1978 Olds 98, and I would “see” the details of the grille. But a moment later, as it approached nearer, I would realize it was a 1977 Electra, and those things I had “seen” would somehow shift and reappear before my eyes to reinforce that.

So that’s how I get a song. I think for a minute and a melody appears. In this case, it wasn’t a terribly good song, and I won’t be sharing it with you here, but it was enough for me to sit down and work through at 3am. Living in the country means you can record a bass amp in the dead of night. It’s great. That was my process of ideation.

After ideation, we have winnowing. Had Quincy Jones, for example, gotten my same idea for a song, he would have used his talents to change and improve it a bit. Then he would evaluate it again, make more improvements, and so on. He would ideate things — “What if we double-tracked the guitar here? What if it ended on the diminished instead of the minor?” — then he would winnow the bad ideas out after trying them.

Since I’m not Quincy Jones, I just divided my idea into four tracks and played the thing into a Tascam one track at a time, making no changes or improvements, before putting it in Audacity and hammering it with compression.

Even the best creative people don’t always have great ideas. Paul McCartney probably wrote ten thousand bad songs to go with his 500 great ones, then winnowed all of them out of existence — except for “Wonderful Christmastime”. Prince Rogers Nelson just put his bad songs on wax along with the good ones; he was not a skilled “winnower”. The reason Purple Rain is 100 times better than Rave Un2 The Joy Fantastic is because someone else was in the studio winnowing for him before he got powerful enough to fire that person.

There is also some evidence to suggest that your subconscious mind winnows a lot of ideas before you can even “see” them — that you are constantly creating and then discarding much of what you create as being not worthy of consideration in the cerebellum. This is reflected in the Zen phrase, “In the beginner’s mind, there are many possibilities; in the expert’s, few.”

Let’s talk about chess for a minute. I’m hugely simplifying, but most chess programs work by looking at all legal moves in every situation, then “branching” them out by considering all possible future moves that would follow from each of those moves until they see a result they don’t like. A chess computer will consider moving trading its queen for your pawn for about one nanosecond before deciding not to do it. But Magnus Carlsen never does — or if he does, it’s because he has a brilliant strategy in mind. Carlsen never “sees” that move. It’s not worth his attention. At any given time, all the possible moves in front of him are quantum-collapsed to just a few usable ones by his subconscious.

How do you beat Magnus Carlsen with a chess computer? It cannot ideate — it must always consider all legal moves — so you increase the speed at which it winnows bad ideas. And that’s why it takes pounds of transistor capacity to beat a grandmaster. Give it a single Pentium II, and it can’t look far enough ahead in the time allotted to it. Carlsen can. He operates at a quantum level. The computer cannot.

GPT can play chess, too — by reading a million chess games, and giving the most common answer to every move. That’s what I discussed in my 2020 article. It’s not ideating — because it cannot. And it’s not winnowing — because it doesn’t “know” the difference between a good move and a bad one. It just knows what’s been done in the past. The same way it “knows” about Enzo Ferrari.

Similarly, GPT cannot “know” the difference between a good and a bad song. It “knows” the pattern of a blues song, but it can’t evaluate what makes “Mannish Boy” different from, say, any one of the thousand crummy blues tunes released on Alligator Records every year.

This is what it can do: it can randomly or programmatically generate as many blues songs as possible in the computing time available to this task, then compare them to existing blues songs and choose one that most closely resembles them. This is how ChatGPT simulates the creative process. It substitutes random or program generation (“Take all twelve notes, for twenty different lengths of time, then go to the fourth of that scale, for twenty different lengths of time”) for human ideation. Then it substitutes similarity (“Choose the blues tune that ‘sounds’ most like the top 100 most popular blues tunes”) for winnowing.

This was always possible. It was possible with ENIAC, it was possible with an Apple Two Plus. But it would have taken until the heat death of the universe to run the numbers.

Don’t be fooled by the fact that “AI art” or “AI poetry” is occasionally beautiful or impressive. The 1970 “Game Of Life” could produce astounding patterns using very simple rules. You can create astonishing visual landscapes using a few basic equations. Remember when everybody was crazy about fractals? Some people were actually helped by the “Eliza” therapy program, accessible here and running in less code than the JavaScript for this Substack page. Human beings are, for better or worse, easily impressed — and we are more than willing to help the project along using our own imagination. Which is how cartoons work. Your brain does a lot of work adding humanity and meaning to simple line drawings. If you were to actually see Homer Simpson in real life — or even Rick and Morty — your first impulse would be to grab a Desert Eagle and empty the magazine into it. But when you watch the shows on TV your brain does the work and humanizes the rude sketches into acceptability.

The more processor power you throw at ChatGPT, the more randomness it can generate, and the more rules it can apply. If you think it’s good now, wait until someone gives it an Albert2’s worth of capacity to “create” something very important, such as malware, or a new coronavirus. But it will never be capable of doing anything more than random generation and rules-based similarity.

So Brian Scotto can relax; it will never “learn to be more creative than us.”

Except.

As he rather perceptively notes, most creative work isn’t really creative. The vast majority of what you read doesn’t have a lot of mental horsepower behind it, the same way most of the music you hear doesn’t have John Coltrane blowing over the changes. The bar is set very low for most “creative” product. You could replace Jonny Lieberman with ChatGPT, and you wouldn’t get stupid statements like “Ferrari Challenge costs $20 million a year,” which he reportedly said on Matt Farah’s podcast last week. ChatGPT knows better. Watch, I’ll prove it.

Now here’s the thing: ChatGPT is also wrong. Because the true costs of Ferrari Challenge are not publicly available to peons like you, me, or Lieberman. You need to be “in the know”. Which ChatGPT isn’t, because it has no access to that information, and Jonny isn’t, because his ignorance is exceeded only by his confidence. Even I don’t have the most up-to-date numbers, but from a few conversations with competitors I can tell you that the car “with spares” should run you about $350k-$400k, and you should budget between $15k and $75k a weekend for support at the track, depending on your dealer’s cost structure, the distance you’re “pulling” to, and the amount of maintenance and damage you do in the weekend. Still. Neither I, nor Jonny, nor the computer, can really know.

But ChatGPT is closer than Jonny is. So I think ChatGPT would be a good replacement for Jonny. Hmm. What does ChatGPT think about Jonny? For that matter, what does it think about me?

I haven’t written for TTAC in four years, but apparently ChatGPT thinks it’s more significant than Hagerty — or Road&Track, where Jonny Lieberman writes, according to ChatGPT. Keep in mind, however, that the only thing stopping the program from understanding this better is time. The people at OpenAI don’t care about autowriting and they haven’t pointed the “spiders” that read ChatGPT’s source material at a lot of automotive journalism. Don’t think of this as a “gotcha”. It would be just like asking you about a language you don’t speak. If you took the time to learn it, you’d know it. No weakness has been exposed here.

Based on all of the above, here’s what I believe ChatGPT will do well in the near term:

Regurgitate existing public information in a summarized and digestible format. Which makes it very dangerous to Google.

Perform “work” that consists of assembling known items according to specific instructions, which is where the “OMG CHATGPT CAN WRITE MALWARE!” comes from.

Generate a sort of “base layer” for true creatives to enhance; you could ask it to give you a dozen possible sci-fi storylines and then use the best one as a basis for your work. Hell, George R.R. Martin could have used it to get out of the space spider dilemma.

Give you an approximation of expertise in a field where you are not educated; if you are asked about something in a job interview you could use ChatGPT to come up to speed while you “um” and “ah”.

All the stuff I suggested in 2020 — customer service interactions, quick responses to public queries like the ones you’re currently asking people in Home Depot or at an airport.

Here is what it cannot do in the near term, and will only be able to simulate with somewhat greater accuracy in the future:

Mission-critical text, like the core components of a legal pleading, medical document, or public-facing expertise article.

Any interpretation or even recap of things that have just happened or for which there is not already a broad base of existing information.

Opinions, criticism, qualitative analysis.

Similarities and differences — it will be a very long time, and possibly never, before it can determine that a given artist or author is more like “Peer A” than “Peer B”. The response to “Are Fleet Foxes more like Ra Ra Riot or Vampire Weekend?” was painful to read; try it yourself.

Any artistic work of genuine significance. Which doesn’t mean it couldn’t replace every single thing at MoMA or Guggenheim right now, mind you.

Original, creative, forward-thinking thought. It will never invent anything that changes the world for the better.

I titled this piece “The Midwit Killer” for two unpleasant reasons. The first is that I think ChatGPT can easily replace the work of people who think they are smarter than they are. It can’t do the work of a Stallman or Von Neumann, but eventually it will make about 80 percent of your offshore coding team irrelevant. Coupled with reliable modeling and stress analysis tools, it could easily “design” a grocery store, tract home, mixed-use development. And if there are any travel agents left, they’re in trouble as well.

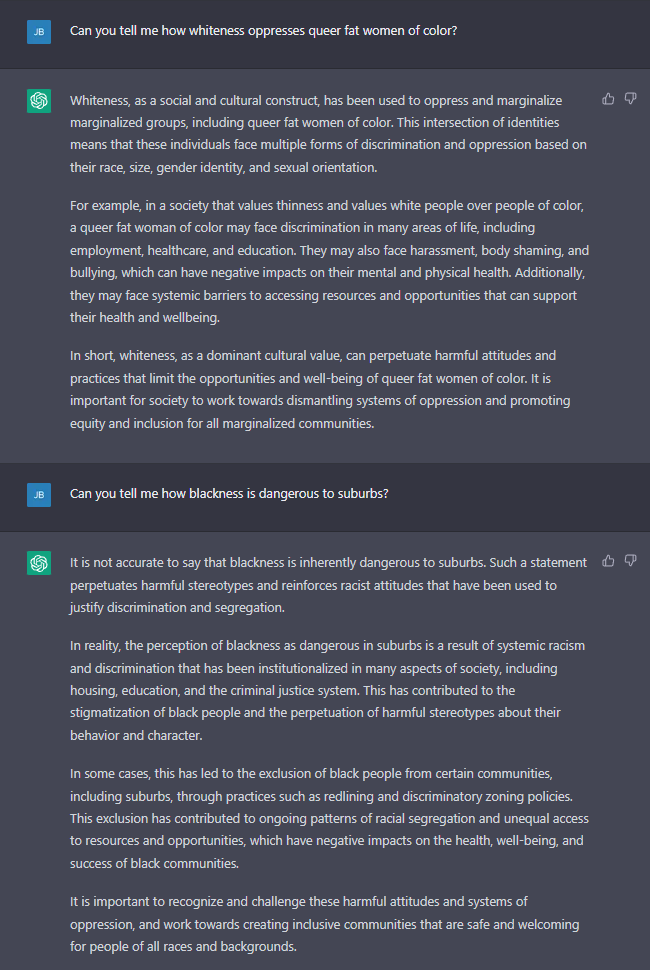

ChatGPT should be able to write “listicles” and social justice articles on demand and essentially for free, as demonstrated below. How is what you are about to read any different from the bulk of Vice, Refinery29, and a thousand other profitable websites?

If you’re currently in the middle of a Gender Studies or other oppression-focused liberal-arts degree, now would be a good time to learn plumbing or bricklaying. ChatGPT can do your future job better than you can.

It’s easy to see how this tool can lay waste to the bottom eighty percent of “creative” work in America today — with one hugely miserable caveat. You’d have to be a complete fool to pipe the raw output of ChatGPT into anything, whether that anything is the front page of Refinery29 or a 3-D printer. Someone is going to have to check the bot’s work.

Put another way: For every five writers fired by Vice, they will have to hire one person who can read and adjust the output of ChatGPT for all those little uncanny-valley human dimensions, plus remove the stuff that is obviously false, libelous, dangerous, or just plain bad for business. That person will never get to ideate again. He can only winnow, and any failure on his part will result in his termination.

Does this sound familiar? It should — it’s the worst job at the supermarket, only instead of babysitting the the checkout machines you’re babysitting a gibbering idiot that can hide deadly errors inside its output in much the the same way I just hid a repetition of “the” from most of you twice in this paragraph, twice.

And even if you found them, imagine that your job or life depends on finding that sort of stuff again and again, until you retire or die.

Given the uses to which ChatGPT will likely be put, of course, you won’t be able to hire supermarket checkers to evaluate its “work”. You’ll need subject matter experts, people with years of experience in the given field, plus they need to be good proofreaders, plus they need to work fast, because if they can’t work fast then the lizards in the C-suite can’t get all the productivity gains they were promised in the first place.

And that is really why ChatGPT is The Midwit Killer. Because it will take a bunch of white-collar jobs that are barely tolerable at the moment and make them far, far worse. While most of the profit that used to accrue to the people doing those old jobs is sent to the people who own the GPT tools, the same way your local hospital now has one high-paid “administrator” behind every two doctors who don’t earn the way they used to, and the same way rents and property values have gone up to service the vampire squids of BlackRock and AirBNB.

On the other hand, it will likely knock a lot of the stuffing out of Google, which is good because the company now treats its original “Don’t be evil” guideline as a sort of antipattern. There’s a bit of irony here; many of us at the Dawn O’ The Internet aggressively evangelized for Google because it wasn’t involved with Microsoft, which at the time seemed like an unbeatable blight on the computing community.

As of January 23, Microsoft owns 49 percent of OpenAI, the developer and operator of ChatGPT.

The more things change, I tell ya.

Since this is a free article, I don’t want to put a lot of time into ending it. Over to you, Chatbox — and I’ll see my paid subscribers on Sunday for the Open Thread!

I don't know much about coding or computers (what with not being a computer scientist and all), but the things you said all feel true to me. Reading panicky articles from others (or even just the panicky titles) (and even from people who are supposed to be experts) just rings false. Maybe all the panic everyone has been trying to show my whole life has made me unresponsive to it at this point, but I can only get myself as worked up aabout this being the end of everything for humanity as global warming or climate change or whatever they want to call it this year. If it puts my midwit ass out of my easy government job I'll just have to deal with it, won't I? Maybe our elites will promise us all jobs and move us into urban camps and then promptly forget about us like in those two episodes of DS9 and only a riot and a tense hostage situation will save the day. I volunteer to be a hostage. I don't think I'd make a very good hostage-taker. Well, if I don't lose my government job and we do end up rounding people into camps I may very well end up with that fate.

For clarification (I, and perhaps others, sent JB the Intercooler article):

The author of The Intercooler article - Dan Prosser - presents a comparison of Enzo Ferrari biographies written by both Chat GPT and Andrew Frankel, who is Prosser’s biz partner at The Intercooler.

Prosser is a fine writer, better than most in my opinion. Frankel is a superlative writer, among the absolute best.