McLaren Artura: (More Than) Everything You Want To Know

Natural Aspiration 01: Thus Spake “Sherman McCoy” re: All-New, Must-Succeed McLaren

Readers, please welcome my friend “Sherman McCoy” to these pages. He had a chance to drive the Artura when I didn’t — but more importantly, he’s also had a chance to talk to independent sources about the actual development costs and real-world implications of the Artura program. His tidbit about “why the headlights are lidded” is worth the price of admission alone. This is a long post and won’t please the tl;dr crowd, for which I apologize. I’m on the East Coast delivering a motorcycle to one of my readers and subscribers; I’ll have a short post tomorrow and something more substantial on Thursday. Thank you — jb

I’ve been having a problem with emails of late.

They cascade into multiple inboxes at every hour of every day; I typically receive over 500 messages daily in my personal inbox alone (to say nothing of those routed to my spam folder). It seems that every merchant with which I have ever transacted, every subscription I have, and every newsletter - including Avoidable Contact Forever! - wants to reach out to me every day.

I could pare things back, of course, but I appreciate the quick bursts of information from every corner of the internet where I’ve left a digital fingerprint, because I don’t want to miss out on anything - FOMO.

A few weeks ago, in between an urgent reminder to buy more toothpaste and a link to a tweet I’d already read, there was an email from the local McLaren dealer inviting me to drive their all-new, entry-level challenger at Atlanta Motorsports Park (AMP), a country club race track situated in the rolling Appalachian foothills an hour north of Atlanta. I’m glad I didn’t miss that email!

The car is called the Artura, and its name is said to represent a combination of “Art” and “Future.” Naturally this brings to mind Cadillac’s Fusion of Art and Science.

My friends at McLaren subsequently reached out on the eve of the event and shared that - “due to unforeseen circumstances” - the test drive program would actually take place on the roads near the track, which was fine with me because I know the roads in the area well, and they offer a greater variety of corners and surfaces than the 2.0 mile, 16 turn road course.

I should note that I was surprised to find that McLaren considers me a “VIP,” given I have never purchased a McLaren, never visited the local dealer, and I’m less engaged with the brand than I am with some of its competitors, namely Porsche and Ferrari. Atlanta-based Porsche Cars North America actively disdains my existence - ask Jack! - and Ferrari failed to invite me to the local launch of its new 296 GTB, which is a direct Artura competitor (despite what McLaren would prefer you believe). Snark aside, I was gratified by the invitation from McLaren and appreciated the opportunity not only to drive the Artura, but to share my observations with Jack’s readers.

Bona Fides & Biases:

I have long wondered, especially in the case of marquee annual (Performance) Car of the Year tests, why road testers evaluating cars don’t establish their bona fides and biases to help the reader assess the writer’s point of view.

Here are mine:

I’m 33, and I’m a lifelong performance car and automotive industry enthusiast. I grew up in the North Georgia mountains near the McLaren drive route, and I spent my childhood reading buff books cover to cover, over and over.

I bought a 993 generation Porsche 911 Carrera out of college. I spent my weekdays commuting in it and my weekend mornings driving it on my favorite mountain roads north of Atlanta; I added a 997 generation 911 GT3 a few years later and used it similarly. After a year of that two car garage, I sold the 993 Carrera - something I regret severely in hindsight - and lost my 997 GT3 in an accident the same day, courtesy of a 16-year-old rocket scientist who made a left turn without yielding. Fortunately, her parents had stellar insurance.

After going from two cars to nil in a few hours, I needed to find new transportation. I test drove an Audi R8 V10, contemplated an Aston Martin V12 Vantage, and inquired about a McLaren MP4-12C. After driving a friend’s recently delivered 991 generation 911 GT3, I forgot the other contenders and bought my own; I still have it, seven years and 49,000 miles later. My total mileage behind the wheel of a neunelfer is just over 70,000.

I purchased, drove, and cherished those Porsches because they delivered the characteristics important to me in a performance car:

Ample engagement / feedback (steering feel, seat of the pants)

Balanced, harmonious control weighting (steering, gas, brake, clutch/shifter where applicable)

Sufficient straight-line performance

Linear, predictable power delivery and aural stimulation (all of my cars have had aftermarket exhausts, as well)

Daily driver capability (I’m a bachelor with a limited commute, but I don’t enjoy second guessing where I might park)

Motorsport “DNA,” however tenuous

As I have aged and matured, I have come to appreciate other attributes in which my cars haven’t necessarily excelled, namely ride quality and comfort.

A final note: I work in finance and follow the business of the automotive industry as closely as I follow the latest, greatest performance cars; this interest informs the section below.

Artura Gestation & Development:

It is no secret that McLaren’s all-new Artura has endured a challenging gestation period.

McLaren Automotive is a small, independent manufacturer conceived scarcely a decade ago to monetize the McLaren Formula 1 team’s image and aggrandize the considerable ego of Ron Dennis, McLaren’s then-CEO. Ferrari the man began selling road cars to fund his motorsport efforts, and Lamborghini the man began selling his road cars to thumb his nose at Ferrari the man; during the intervening decades, the Italians’ reputations have been buffed and burnished, providing them with inestimable brand capital and massive financial capital to continue developing their products and enhancing their market positioning.

Meanwhile, McLaren sought to compete with Ferrari, Lamborghini, and other supercar purveyors from the outset, and to do so on a level playing field. The new British manufacturer had to engineer and build competitive products while developing supplier networks while fostering a brand identity while establishing a global dealer network while balancing production output against the need to protect residual values and ensure quality control for customers … and so on. It is an extraordinary challenge to start a carmaker ex nihilo, as management - and shareholders - at Rivian and Lucid have recently learned.

Results thus far have been mixed; while it is now a credible contender in the supercar firmament, McLaren’s nascent brand image couldn’t support rapid iteration across a confusing array of products that shared identical or very similar core components: a carbon fiber tub, a twin turbo V-8 delivering power to the rear wheels via a 7-speed dual-clutch transmission, and a hydraulic steering rack. Furthermore, financial reliance on limited production, high margin “Ultimate Series” cars asking seven figure prices became greater over time: the P1 hybrid preceded the brutalist Senna, which was followed in quick succession by the F1 road car tribute Speedtail and the open-air Elva. The top-drawer cars began to sputter as their introductory cadence quickened. When the Elva arrived in late 2019, McLaren reckoned they could sell 399 units worldwide. Output voluntarily fell to 249 units and then 149 units; the company remains engaged in a search for Elva buyers nearly three years after the car’s debut.

Initial product planning timelines penciled the arrival of a replacement for the aging, entry-level 570S (introduced in 2015) in 2020; instead, McLaren spent the year cutting staff, cutting production, and maneuvering to protect its financial position. That’s understandable in the context of COVID-19, but other manufacturers - e.g., Ferrari and Lamborghini - were more resilient.

McLaren officially launched the Artura in February of 2021 by way of a brief video. Bizarrely, McLaren PR leadership chose to launch their new volume model hours later on the same day that Porsche released its own video introducing the 992 generation 911 GT3, AKA the Death Star that commandeers the attention of enthusiast-oriented automotive media and seems to win every comparison test. I’m baffled as to why - and how - McLaren let that transpire. Three months later, the press embargo on the new 911 GT3 broke, and breathless impressions of Porsche’s latest winner flooded every car review website and YouTube channel, with customer deliveries beginning in the third quarter of 2021.

All quiet on the Artura front during that time, as McLaren were otherwise occupied during the balance of 2021 (and 2022):

A sale-leaseback transaction covering the iconic, Norman Foster-designed McLaren Technology Centre and ancillary facilities

Spinning off McLaren Applied Technologies

Hiring a new, ex-Ferrari CEO - Michael Leiters (which means McLaren is likely not for sale, at least now)

And … injecting more capital

Amid this corporate intrigue, it’s understandable - albeit still unforgivable - how McLaren lost nearly 18 months on the Artura product timeline, which cost brand momentum, revenue, dealer goodwill, and allowed competing marques to bring their all-new, mid-engine V-6 junior supercars to market first: the Maserati MC20 and the Ferrari 296 GTB.

An additional piece of context: McLaren eventually, ultimately, finally put the Artura in front of journalists in spring of 2022 at the Ascari Race Resort in Spain. McLaren scrapped a planned October 2021 press launch at the last minute, citing software issues, and there are rumors that this was a precipitating factor in Mike Flewitt’s ignominious departure the same month. The much-delayed 2022 media event featured alarming software and reliability gremlins, including multiple “thermal events.” A “thermal event” is Ronspeak for “fire.”

I read and watched most of the press reviews, which were generally positive about the (pre-production) car, if cautious of its potential foibles in production guise. A few of them featured elements that were, frankly, dismissive of or disrespectful toward McLaren.

Chris Harris repeatedly interrupts and marginalizes his former Autocar coworker Jamie Corstorphine, who is a McLaren executive:

Jethro Bovingdon, who happens to be married to McLaren Public Relations Manager Laura Conrad (!) saw fit to spice up his Artura video by splicing in some footage of him driving the competing Ferrari 296 GTB (start at 2:30). I bet he slept on the couch for a few nights.

It goes without saying that Ferrari or Porsche - to name just two - would never receive this treatment from journalists.

While the Artura project was in apparent hibernation, the remainder of the McLaren model lineup stagnated: Output of the final variants of the entry-level “Sports Series” - the 570S-derived 600LT Coupe and Spyder plus the run-out edition 620R - slowed to a trickle. The “Super Series” 720S family is over five years old and is now expected to soldier on for a few more years with the aid of a previously unplanned facelift. The overmilked cash cow “Ultimate Series” is on hiatus until 2025. The McLaren GT - remember that one? - may be the most “exotic” car McLaren makes, since no one bought it; I have seen precisely one on the road, making it a rarer bird for me than the Senna, which was limited to 500 units globally.

Against the backdrop of corporate challenges I have presented above, it is not hyperbolic to claim that the Artura is an existential car for McLaren: The Artura must succeed to ensure McLaren’s continued existence. It must meet sales expectations in a crowded marketplace on the cusp of a global economic slowdown. It must provide dealers with new products to sell and service. It must validate McLaren’s all-new V-6 hybrid architecture that will underpin its go-forward model range during the 2020s. It must provide customers with reliability and build quality they would receive from a competing marque, and it must protect those customers with robust residual values so that they will continue being McLaren customers.

So … what were my impressions of the car?

Exterior:

McLaren has employed several chief designers during the company’s brief existence, each developing their own interpretation of the brand’s design language. The company’s debut product - the not so evocatively named MP4-12C - arrived with bodywork that appeared sterile, anodyne in comparison to its contemporary competitor, the bella macchina Ferrari 458 Italia. McLaren responded to the criticism with a swift facelift; the updated car featured a new, angrier visage with boomerang shaped headlights, a black panel on the rear bumper, and a new nomenclature - it was called the 650S.

Opinion is divided regarding the Artura’s appearance: Some commentators think it looks like a store brand supercar, whereas others find it a welcome continuation of the visual DNA McLaren has begun building.

I’m in the latter camp.

To my eyes, this is the best integration of the boomerang headlights - bisected by the “hammerhead” swoop carrying the daytime running lights - to date. This view showcases the car’s nipped waist as the aluminum bodywork flows over the rear haunches. The roof is available in body color or black; on any car with such an option, I have a strong preference for body color.

From the rear, the car has plenty of tumblehome, the reliable signifier of supercar proportions. The rear mesh panel recalls the P1’s rear end, and the imposing twin exhaust pipes are in a tailgater’s line of sight.

The “chimney” above the combustion engine is a feature McLaren is, apparently, proud of. I think it looks awfully industrial and out of place in any car, certainly one commanding north of $250,000. It also produced a noticeable heat haze in the rear-view mirror.

The flying buttress detail is best showcased from this angle; it’s an elegant design feature, and I hope the forthcoming Spyder variant retains it. The swooping intake inlet below is a beautiful, complex shape with crisp edges rendered in “superformed” aluminum.

In profile, it’s a striking body with a resolutely cab forward layout. From the side, the Artura appears far more refined than the now-retired 570S, which looks like a dated kit car on a comparative basis. The Artura has supercar road presence, but there is versatility on offer: Sober paint colors would allow it to pass (almost) as inoffensively as a C8 Corvette, whereas exuberant selections afford the opportunity to peacock with the best exemplars of the breed.

I would choose either Flux Green, the launch color (above), or McLaren Orange, the brand’s heritage color (below).

The small rear window is a piece of subtly curved glass, and I expect the replacement cost would be fearsome. It made me think of the not-a-Ferrari Dino’s extravagantly curved rear glass; I’m sure neither Ferrari nor McLaren would appreciate this observation. Note also that the rear bodywork is one large piece of aluminum. Avert your eyes from the odious chimney.

McLaren had four Artura examples available for the event; I looked over all of them to get a sense of panel gap and shutline consistency across an admittedly small sample. Happily, no issues reported.

Interior:

Like all McLaren offerings, the Artura features “dihedral” doors that open upward. The unorthodox doors and McLaren’s carbon tub architecture - which necessitates high, wide door sills - conspire to make ingress and egress more challenging propositions than they are on conventional vehicles. New McLaren model introductions frequently include boasts that the opening aperture has been expanded to ease entry and exit; if that’s true, the improvements are only marginal. It is challenging to get into or out of the car with any degree of personal elegance.

I drove a car with the base “Comfort” seats, which provided more lateral support than their dowdy appearance indicated - no flashy lashings of carbon fiber or deep bolsters. The seats offered a range of power adjustment, but the motors powering their movement operated at a glacial pace. Similarly, the steering column is electrically adjustable, albeit slowly. I would prefer manual for both - it would be quicker, lighter, and not out of character for a lightweight supercar. Better still, if I were speccing a car, I’d probably opt for the more aggressive “Clubsport” seat. Unfortunately, there were none on hand during the event.

Once my passenger and I were settled, I started playing with the seat and steering column adjustments to dial-in the driving position. My passenger was a young, journeyman driving instructor with a professional background in grassroots motorsport, and he proved to be more co-pilot than chaperone. Although deeply knowledgeable about the Artura, his only affiliation to McLaren was the logo on the shirt they gave him to wear.

I am 5’8” on a good day, and I have a relatively long torso and short legs. I like to sit as low as possible and fairly close to the wheel with my radius and ulna resting atop the rim while my arms are extended and my right foot is fully depressing the brake pedal. After exploring the full range of adjustments, I settled on an acceptable, but not ideal position. As a consequence of this compromise, I felt that the entire dashboard and the dash screen itself were oriented more toward my chest than my eyes. Headroom was a non-issue for me and my co-pilot - we both had plenty of room to spare; McLaren customers are necessarily wealthy, and wealthy men (yes, McLaren customers are mostly men) tend to be taller than average.

The Artura has a relatively austere cabin, with a simple dashboard featuring the instrument panel screen and a center tablet controlling the car’s infotainment system positioned in portrait orientation. McLaren’s old IRIS system was laughable; a quality infotainment user interface is table stakes for any new car in 2022, in my view. I’ll have to give McLaren the benefit of the doubt on the new central screen, because I couldn’t be bothered to spend time fiddling with it. The cabin environment is a far cry from the intricate detailing found on 992 generation 911s, contemporary Ferrari models, and even the aged Lamborghini range. The impact of this was worsened by the base interior scheme of the car I drove, which was like a black cave furnished in middling leather and some sort of synthetic suede - I’m unsure if it was Alcantara, Dinamica, or another brand - of a quality grade lower than that used in competitors. There are more luxurious appointments available, but none of the cars on hand were so equipped.

McLaren employs shift paddles that operate on a rocker switch, à la Formula 1 cars, which means you can pull on the right for an upshift or push on the right for a downshift, and vice versa. Unfortunately, they give off a plasticky click at every engagement. The paddles are lovingly shaped and textured, however.

The Artura debuts new toggle switches for the car’s drive modes located on the upper corners of the instrument binnacle, Powertrain on the right and Handling on the left. The drive mode options include Comfort, Sport, and Track, and the Powertrain and Handling settings can be configured independently, as with older models. McLaren highlighted this new switch placement during the car’s launch. I will concede that I’d rather have these selectors near the wheel rather than on the wheel - in Ferrari fashion - but I found this implementation lacking. The switches are ugly, and they look - and feel - cheap. They don’t offer any positive engagement or clicking when they’re manipulated, so you have to look at the screen to confirm an adjustment. The conventional switchgear, often a problem for low volume manufacturers, met with no issue.

My car was optioned with the upgraded Bowers & Wilkins sound system. I am a fan of B&W for their sonic performance, as well as their outré designs, and the brand profile meshes well with McLaren’s. Despite this, I wanted to hear only the car and my co-pilot, so we left the B&W hi-fi turned off. Unfortunately, we heard from the speakers anyway. There was a distinct rattle emanating from a speaker located above the passenger’s right shoulder at moderate to aggressive throttle openings around 3,000 RPM. Naturally, I was assured I was driving a not quite production spec car, and that this niggle had been resolved. I hope so…

Visibility is tremendous. The windshield plunges forward to an ultra-low scuttle, the greenhouse is airy in all directions, and the flying buttresses help minimize blind spots. The side mirrors are of substantial size, and someone at McLaren had already adjusted them appropriately before we began driving. Finally, the view rearward is expansive, despite the smallish rear window and the distortion from the chimney. Upon reflection, I cannot recall ever driving any closed roof car with superior visibility.

I drove in the afternoon, fortunately before a thunderstorm blew over North Georgia. My tester had spent the entire day either driving or parked on an ocean of scorching blacktop at AMP. Despite the size of the greenhouse, the heat radiating from the car’s Power Unit, brakes, and tires, my car’s black roof, high ambient temperatures (90+ degrees), high UV index, and high humidity, the Artura’s air conditioner blew cold immediately. No mean feat for an all-new, pre-production car from a boutique manufacturer that managed to sell just 2,138 cars in 2021.

Chassis:

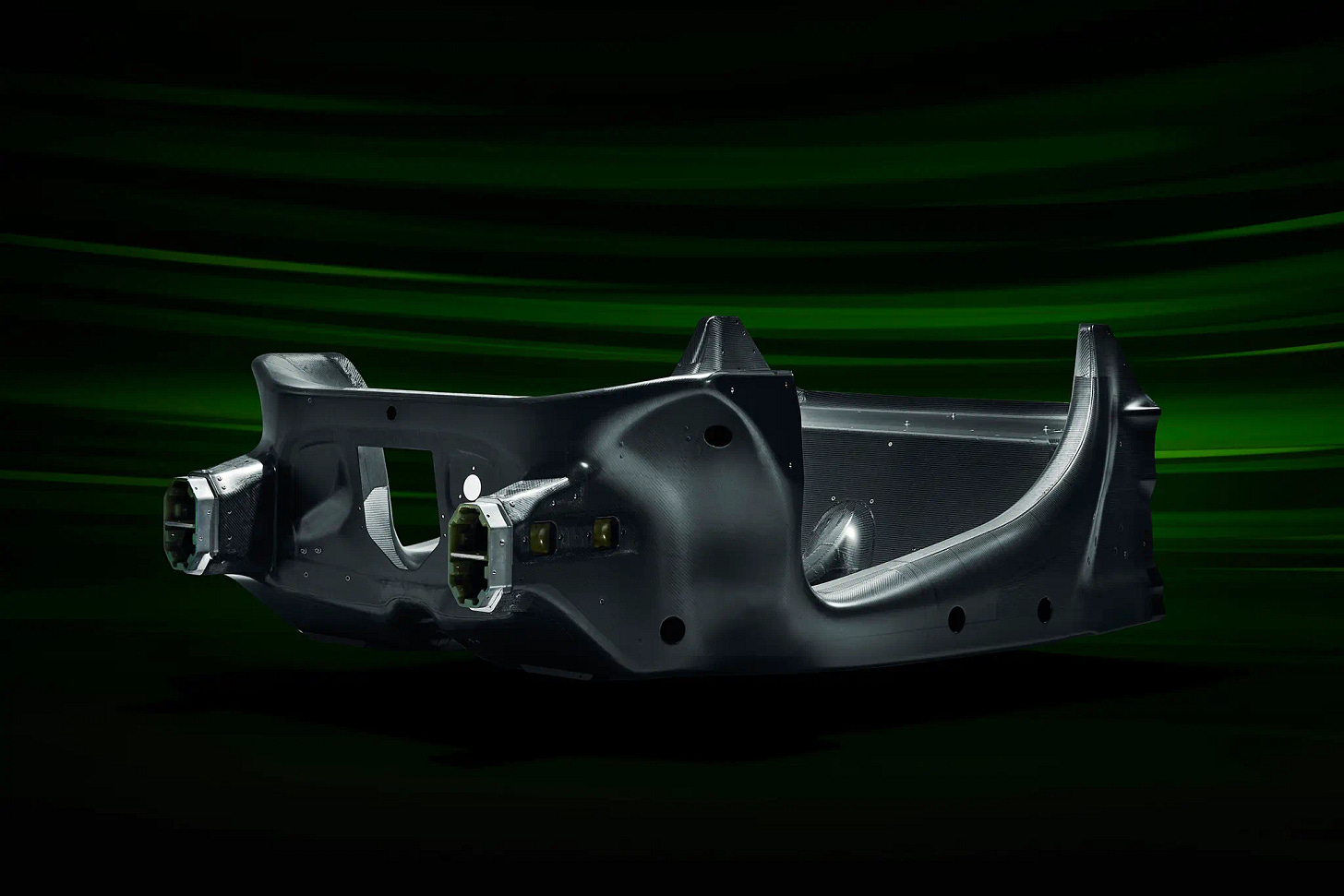

McLaren’s greatest brand signature is chassis construction based on a carbon fiber tub. Famously, McLaren was the team that in 1981 introduced the first Formula 1 car with a fully carbon fiber monocoque. Barely a decade later, McLaren debuted the cost-no-object F1 road car with a carbon tub; if you consider the little-known Jaguar XJR-15 a “road car” - debatable - it just pipped McLaren to the road car milestone. All subsequent McLarens have been built with the same philosophy.

There are numerous benefits to carbon fiber construction, but it’s not without drawbacks, particularly for road cars. Carbon fiber chassis are stiff, lightweight, and strong. If I had to have a high speed crash in a road car, I’d prefer to be in a car with such a safe, strong tub. Shortcomings include cost and time to repair, increased insurance premia (since repairs are pricey and a car could conceivably be totaled in a relatively minor incident), challenges with respect to isolating and dampening noise, vibration, and harshness (NVH), and resonance throughout the tub, as well as the difficulties the high, wide sill presents.

McLaren claims the Artura’s tub - the new McLaren Carbon Lightweight Architecture, which was designed to accommodate and safeguard the battery pack - is stiffer and lighter than its predecessors. The tub weighs 181 pounds.

The car glides beautifully over corrugated surfaces and potholes, and I drove over loose gravel more than once out of curiosity to find whether I’d hear it snare drum off the bottom of the tub - no such problem (or any other NVH problems aside from the rattling B&W speaker). Traction is absolute in all circumstances I encountered, and the car is agile and nimble despite a 3,303 pound curb weight - yes, McLarens are typically lighter than their peer set, but the hybrid does add weight versus earlier cars (see greater detail below) - and two adult male passengers.

I repeated the drive route in my GT3 after we concluded to gain a little more context; this only enhanced my appreciation for the capabilities of the car’s chassis. The Artura travels much faster everywhere and rides far better.

But there is a demerit, at least for me.

While the chassis is obedient, it doesn’t relay as much information as I’d like back to the driver. There’s less feedback of a visceral nature - the car whispers where it could shout. I’m curious to what extent the Clubsport seats would alleviate this gripe.

Steering, Tires & Suspension:

McLaren is one of the few performance car manufacturers that still employs hydraulic steering; Lotus is another, at least for now. Ferrari, Lamborghini, and Porsche have long since abandoned hydraulic steering for the efficiency gains and driver assistance options that Electric Power Assisted Steering (EPAS) affords.

I was excited to experience McLaren’s latest effort in this regard, as steering feel is the single most important enthusiast car characteristic in my book.

It was a bit of a letdown. The steering weights up - and unweights, crucially - in sublime fashion, but it doesn’t tell the driver much about surface texture or grip level, even as speeds increase. The steering system responds slightly differently across drive modes: There is a noticeable on-center vagueness in Comfort mode, but this disappears in Track mode. We skipped the middle-ground Sport mode because I wanted to focus on the bookends. I understand that the hydraulic pressure in the steering system changes between modes to create these distinctions.

Chris Harris described it thusly:

As for the steering, it’s like tasting real, Mexican sugar Coca-Cola after a month of drinking the new healthy rubbish: a genuine ‘wow, this is how things used to be’ moment.

While it’s a nice simile - I wish I’d thought of that! - I have to disagree with him. The Artura’s steering doesn’t offer the gritty, granular detail for which I was hoping. I was expecting something on the level of a Lotus Evora, but the Artura is nowhere near Hethel’s effort. According to McLaren, the Artura’s steering system is “fully redesigned;” I’d like to go back to the steering system from the 570S.

I don’t think the car’s tires contributed to my disappointment, either. I am a Michelin man in many aspects of my life: tire of choice, approach to life, and Substack avatar. McLaren has a partnership with Pirelli and engineers its cars accordingly. My Artura wore bespoke Pirelli P Zero PZ4s in staggered 235/35ZR-19 (front) and 295/35ZR-20 (rear) fitment. If anything, a wider front tire would probably offer less feedback as a trade-off for greater front grip. The rears never faltered when asked to transmit 680 hp and 530 lb-ft to tarmac. There is a racier P Zero Corsa option available, but the road tires that McLaren specified for the car are beyond adequate. The Pirellis are also quiet for supercar tires. My direct basis of comparison likely flatters the Italian hoops, but on the same roads there was far more road noise from my GT3’s Michelins.

The Artura has double wishbones on the front axle and an all-new multi-link suspension on the rear axle. McLaren claims the front axle suspension specification reflects that fitted to the 600LT; I haven’t experienced the LT, but I hope it would offer greater feel. Turn-in was incisive, but I would have preferred fractionally more body roll than exhibited, because it helps signal the driver about how the car is behaving. The Artura does not feature the trick, hydraulically interlinked suspension that other “Super Series” McLarens have (the Artura - which replaces the “Sports Series” 570S - is a “Super Series” car; the “Sports Series” appears dead). The Artura instead is conventionally suspended, with adaptive dampers, coil springs, and anti-roll bars.

“Power Unit” & Transmission:

The most important update that the Artura brings is an all-new drivetrain.

The all-new engine is a 120 degree 3.0 liter V-6 with twin turbos nestled in its vee that develops 585 hp - or 195 hp / liter - and 431 lb-ft of torque and redlines at 8,500 RPM. The engine block, cylinder heads, and pistons are all-aluminum; McLaren makes reference to the engine’s block and heads having 3D-printed cores, asserting that this “technology [is] more typically used in Formula 1 than road cars.” McLaren’s PR guff fails to mention that McLaren has never made its own Formula 1 engines and would rather buy them from someone else. McLaren is a Mercedes customer at the moment, but they have been happy to purchase from Renault and Honda over just the past five years! Obviously, a Ferrari engine in the back of a McLaren Formula 1 car is beyond the pale.

The all-new electric motor and battery contribute 95 hp and peak torque of 166 lb-ft. The e-motor is apparently the first “axial flux” motor in a series production vehicle; the conventional alternative is a radial flux motor (magnets surrounding a rotor). “Axial flux” sounds like a type of music I’m already too old to understand. Alloyed together, the combustion engine and electrical motor form the Artura’s “Power Unit,” in Formula 1 parlance, and offer a combined power output of 680 hp and 530 lb-ft of torque. Power is delivered through an all-new 8-speed dual-clutch transmission, which integrates McLaren’s all-new electronic locking differential. The e-motor sits in the transmission bell housing.

Save for the McLaren F1, all prior McLaren road cars had a 90 degree 3.8 or 4.0 liter twin turbo V-8 with origins in the 20th century; curiously, the foregoing V-8 was not direct fuel injected, which is the likely reason why no preceding McLarens were fitted with gasoline particulate filters, although the Artura does feature direct injection and particulate filters. Excepting the McLaren P1 (375 units) and Speedtail (106 units), the Artura is the first hybrid offering from the brand. The Artura’s locking differential is also a first for the brand; all previous cars featured an open differential that would brake the inside wheel to mimic the effect of a locking differential; McLaren’s marketing team amusingly dubbed this feature “Brake Steer,” a reference to a notorious, ingenious piece of Formula 1 trickery.

The new V-6 is 110 pounds lighter than the outgoing V-8 and has a lower center of gravity given its wider vee angle; furthermore, it’s 7.5 inches shorter and 8.7 inches narrower, accounting for the turbos aside the V-8, which lowers the car’s polar moment of inertia by moving mass toward the center of the car. I suspect the smaller engine footprint freed up space for the all-new multi-link rear suspension, as well. On the other side of the scale, the hybrid system adds 287 pounds of weight:

Power-to-weight ratio w/ hybrid: 3,303 lbs / 680 hp = 4.86 lbs / hp

Power-to-weight ratio w/o hybrid: (3,303 lbs - 287 lbs) / 585 hp = 5.16 lbs / hp

Nevertheless, the inclusion of the hybrid element is accretive to the car’s power-to-weight ratio, and McLaren credibly claims that the e-motor sharpens low-RPM throttle response with “torque infill.” McLaren’s earlier V-8 efforts received criticism for turbo lag. While the arrival of the turbos’ boost is perceptible as the Artura builds revs, there’s sufficient low down motivation that the driver isn’t left waiting on the turbos to spool. The additional cog helps, too.

This slate of all-new components is ambitious, expensive, and demanded significant developmental resources. Absent delays in the Artura’s development, McLaren would have had the car on sale years before the Maserati MC20 and Ferrari 296 GTB arrived. The competing Ferrari also has a hybridized 120 degree 3.0 liter V-6 with twin turbos nestled in its vee; Ferrari’s Power Unit has a combined output of 819 hp and 546 lb-ft of torque and redlines at 8,500 RPM. Maserati’s MC20 has a non-hybridized 90 degree 3.0 liter V-6 with twin turbos that produces 621 hp and 538 lb-ft of torque and redlines at 8,000 RPM. Maserati has a hybridized variant in the pipeline and has outlined a plan to offer an EV MC20 on the same platform. Naturally, Maserati - the member of the trio that hasn’t raced in Formula 1 since the 1960s - incorporates Formula 1-style turbulent jet ignition into its new V-6, whereas Ferrari and McLaren, the stalwart constructors with the longest unbroken histories of competition in the sport’s uppermost echelon, do not offer such technology in their new engines.

Engineers in Woking must be smarting over ceding first mover advantage to Ferrari and Maserati. The Italians bookend the Brit in terms of power output; McLaren pretends they aren’t competitors, but every guest at the event was discussing the relative merits of the trio (including even some wearing McLaren gear). The Artura is also in the middle in terms of price: Maserati asks from $216,995, McLaren starts the bill at $237,500, and the bloodsuckers at Ferrari will get out of bed for as little as $322,986. I am quite confident that the Artura is the lightest of the trio, at least.

When I was driving the Artura, however, the only numbers I was thinking about were the rapidly whirling figures on the dash ahead of me. After a few exploratory miles, I was accustomed to the Artura’s controls, and my copilot and I made a right turn onto a road I know well and had driven earlier, en route to the event. On a section of road that isn’t particularly long, isn’t particularly straight, and isn’t particularly flat, I dispatched four gears and was midway through the fifth - the ratios are very short, only the top cog is an overdrive, and I suspect the final drive is rather short too - PDQ. My patient co-pilot calmly asked if I knew how fast I had been going when I slowed for the left hand turn rapidly arriving through the wide-screen windshield. I thought I had seen the speedometer click over into triple digits just before I braked, and I shared that with my co-pilot with unshakeable confidence, maybe even a touch of smugness.

I was actually traveling 30% faster. I detest the journalistic trope about looking down at the dashboard in shock regarding the speed of travel, but it genuinely happened to me. I am loathe to employ another trope and say that the car is too fast for the road, but making it quicker wouldn’t make the car any better, and it would need to be far slower before it suffered for it. Of course, all future McLarens will be more rapid…

McLaren claims the car will surpass 60 MPH in 3.0 seconds; I’m sure the instrumented tests will be several tenths quicker. The 0-124 MPH sprint is pegged at 8.3 seconds, and that also seems conservative. The quarter mile estimate is 10.7 seconds, and I’d guess the trap speed would be north of 140 MPH given the power figure. I’m looking forward to Car & Driver strapping on the timing gear.

One caveat about the car’s acceleration: There was a noticeable delay on full power 1-2 and 2-3 upshifts, something on the order of what you’d expect from a torque converter automatic rather than a brand new 8-speed dual-clutch ‘box. I was told this is a pre-production software issue related to the interaction of the e-motor, the traction control, and the gearbox. McLaren claims that the car can shift in ~200 milliseconds. The lapse between pulling a paddle and the actual activation of the shift is briefer than any car I have driven, including Porsche’s vaunted PDK gearbox (PDK shifts are ferocious - yet still crisp - at their fastest, but there is a perceptible delay between commanding the shift and actually receiving it). There is also a surge of torque - likely the e-motor - on full throttle upshifts. It adds a bit of drama, but it makes the tardy 1-2 and 2-3 shifts feel heavy-handed. This happened in both Normal mode and Track mode; again, I elected to skip over the Sport mode in between.

At one point, there were some grass clippings in the road, which my co-pilot knew about because he had been a passenger on the same loop all day. This provided an opportunity to slow down and experience the car’s electric only mode, activated via a few quick flicks of the Powertrain mode selector. Instantly the car was eerily quiet and the throttle far less responsive, but still no NVH intrusion detected; after a few more clicks a few corners later, the combustion engine fired on demand, and we were underway at pace once more. Although the Artura is a plug-in hybrid, the engine can be used to charge the battery, so the car will always have electric only capability available. This must be the case, since the e-motor also handles reverse. The battery will charge to 80% in ~2.5 hours at home, per McLaren. While the electric only option is always at hand, the range is only 11 miles (the battery has up to 7.4 kWh of energy to deploy). This is unimportant to me - and likely many other American consumers - but the car is a global product and there are a growing number of markets in which this is valuable - necessary even - for regulatory reasons. I suppose this functionality could improve neighborly relations by obviating early morning cold starts, but the car isn’t particularly loud, even with the sport exhaust fitted to my test car (the newly fitted particulate filters act as an additional muffler on top of the turbos, catalysts, and conventional muffler).

That’s not to say the car doesn’t sound good. The induction noise is stirring, particularly with the throttle fully open, and it builds in a hardening crescendo to redline. I am particularly demanding with respect to how a car sounds; my GT3 has open pipes, and while I love them, not everyone does: My ears were burning when I read this R&T piece that Jack wrote after I visited him in Ohio a few years ago. Speaking of flat-sixes, the Artura actually sounds a bit like a Porsche in the upper rev registers, at least inside the cabin; perhaps it’s the wide vee angle. The exhaust note is less tuneful and less authoritative than many owners will like, but the aftermarket can help ameliorate that problem.

All of the exciting, all-new engineering invested into the Artura’s Power Unit and transmission will be quickly forgotten if the car doesn’t prove reliable. Seasoned McLaren customers have reason to be wary based on earlier cars and Artura press reviews. Ferrari has set a high bar in terms of warranty and service, and McLaren has been forced to follow suit: Artura buyers will receive a five year vehicle warranty, six year battery warranty, and a three year service plan.

The Artura delivers an EPA-rated 17 MPG city and 21 MPG highway. I expected a stronger highway figure based on the car’s low drag body, the 3.0 liter engine, and the 8-speed transmission.

Braking:

My Platonic Ideal of performance car brake pedal would be fairly wide, exceptionally firm, as if there were a brick under the pedal, and able to be modulated by flexing only the big toe of my foot.

McLarens are notorious for having “long” brake pedals. Not “long” in the sense of fade, rather in the sense of modulation. McLarens are also well known for having a “creeping” idle, i.e., they move rapidly in first gear off idle. This coupled with a brake pedal with a bit of a dead zone at the top of its travel made it challenging to maneuver in a parking lot. I acclimated quickly, however. Despite the fact that the Artura is a hybrid, there is no front axle brake regeneration, which is a boon for brake feel.

The lack of front axle brake regeneration also affords a sizable, albeit shallow frunk. Based on the eye test, I think it could easily accommodate a full-size carry-on bag and another smaller bag.

The car’s braking performance was unimpeachable, and I never came close to outrunning the car’s brakes, even when I was going much faster than I thought I was. Carbon Ceramic discs are standard, and calipers are forged aluminum: 15.4 inch and 6 piston monobloc (front); 15.0 inch and 4-piston (rear).

Despite the powerful braking abilities, I did have a problem with the pedal itself.

I found the pedal a little narrow for my liking, and I also found it felt slightly convex under foot. In the picture above, you can see that the sides of the throttle pedal, which are straight, are not parallel with the sides of the brake pedal. I elected not to debase myself by getting on my knees to examine the pedal in forensic detail, but those experiences didn’t inspire confidence, particularly in someone else’s exceptionally rapid $250,000+ car. For context, I’m a size 10D and was wearing moccasin style driving shoes.

Finance / Economics:

Before concluding, I wanted to delve into the financial and economic aspects of the Artura’s development. I have a buddy who has spent the past decade working in finance functions at a variety of manufacturers - some big, some small. Over time, his co-workers have included people from many OEMs, including McLaren (and Ferrari, for that matter).

I asked him to clarify a few hypotheses for me; the discussion was illuminating:

The phrase “all-new” appears repeatedly throughout this article, because the Artura is genuinely an entirely new proposition, a reset for McLaren. All cars from the past decade were ultimately descendants of the MP4-12C, whereas the Artura represents McLaren 2.0. I guessed that the total budget for the car verges on $1 billion. His more informed opinion places it on the order of $800 million, divided evenly between the Power Unit and the remainder of the car. A portion of the assumed outlay will be amortized over future products that evolve from the Artura; there is an element of discretion on McLaren’s part regarding the specific allocation.

The genesis of the V-6 combustion engine is unclear. Nowhere in McLaren’s marketing materials does the phrase “in-house” appear regarding the engine, but neither does Ricardo - the builder of the sunsetting V-8 engines - appear. Curiously, the aforementioned Jethro perhaps sheds additional light in his first-drive write-up for Evo Magazine. Bovingdon reveals that BMW helped develop the powertrain, and he further goes on to specify that the new V-6 is “once again manufactured by Riccardo [sic]” - indeed, the established journalist writing for one of the top automotive media outlets worldwide, who happens to be married to a McLaren PR exec, managed to misspell the name of the carmaker’s engine building partner. There are other rumblings about a McLaren tie-up with the Bavarians: Georg Kacher - in Sherman’s opinion the most connected and best-resourced industry journalist - recently wrote about a mooted electric supercar collaboration. Of course, the companies have worked together in the past, and did so to terrific effect, on the Paul Rosche-penned V12 powering the McLaren F1. Alternatively, my industry friend believes it’s conceivable that McLaren simply purchased an ill-fated engine project from someone else and repurposed it for the Artura.

Tooling expenses, which are a meaningful budgetary component for higher volume manufacturers, are less instrumental for McLaren generally, and significant elements of McLaren production are performed by hand. As for the interior deficiencies I found, McLaren’s relationships with suppliers are probably responsible. Based on McLaren’s short history, low production volumes (averaging 41 cars per week in 2021), and challenging creditworthiness, the brand lacks the clout to engage with tier 1 suppliers, so McLaren is forced to work with tier 2 suppliers instead. Tier 2s are typically unable to offer the quality and sophistication of materials that Tier 1s offer, particularly in terms of interior surfacing.

A final, fascinating supplier anecdote: While I’m sure there is a plausible aerodynamic explanation for McLaren’s election to tuck their cars’ headlights under the front bodywork, like a predator’s menacing eyes, the real reason is more pragmatic. Shielding the headlight from direct sunlight helps prevent premature yellowing and peeling on the Tier 2-supplied lenses.

As for Ferrari, my friend estimated that the budget for the all-new 296 GTB, which rides on a more conventional aluminum chassis, was in-line with the Artura budget. Ferrari, however, delivers 3.0-3.5x the output that McLaren produces (on a total annual basis), and Ferrari’s 296 asking price begins $85,000 higher versus the Artura. Ferrari material costs as a percentage of MSRP are typically 35% - 40%, which leads to industry best operating margins.

Ferrari - inclusive of its wholly owned Formula 1 team - trades publicly and is worth ~$40 billion at time of writing, which is staggering in light of having shipped 11,155 cars in 2021 (production was ~5.2x McLaren’s last year). McLaren - which owns 85% of its Formula 1 team that was valued at $741 million in late 2020 - is probably worth low- to mid-single digit billions in a hypothetical IPO scenario.

Summary:

My impressions regarding the Artura were mixed, obviously. The car’s highlights are triumphant, and McLaren deserves credit for shepherding the car through the storms of the past few years. The areas in which it’s lacking are mostly details, but that’s still disappointing because a boutique manufacturer imbued with a Formula 1 team’s drive for success and engineering exactitude should sweat the minutiae.

The exterior is a robust execution of the junior supercar silhouette. The slinky, shrink-wrapped bodywork adheres to - and furthers - the brand’s developing aesthetic codes, notwithstanding the lamentable chimney. The spartan interior is a weaker effort, but some of those issues could be addressed with ease: Plasticky switches, dainty brake pedal. The puzzling ergonomics could be resolved when the car is facelifted, and the buzzy speaker is hopefully a one-off.

The Power Unit’s performance and flexibility are astounding, but no one - perhaps including McLaren - can speak for its long-term reliability. I didn’t expect it to provide an inspiring soundtrack, but it did (and I am a demanding grader on this subject). The chassis capability is extraordinarily high, but I’d trade a little of that back to McLaren for greater feedback through the seat and the steering wheel; the subpar steering feel was my greatest disappointment with the Artura. Most worrisome, McLaren is particularly proud of the car’s steering. I don’t think it’s good enough.

There were two 765LT owners from Tennessee who had made a day trip to North Georgia to drive the Artura; both made positive noises about the car and said they’d probably place orders. I hope they do.

I hope that McLaren can resolve the faults that left me conflicted regarding the car, and I hope that McLaren will continue to push its more established competitors to innovate and improve. I hope that the Artura, coupled with new executive leadership and capital for continued growth, secures McLaren’s future and ushers in a prosperous era for the marque; not least so that they’ll be around to send me more emails.

(All photos courtesy of McLaren PR)

That's not my understanding of how the automotive supplier tiers work, having worked for DuPont, which operated as a Tier 1, Tier 2, and Tier 3 supplier. The tier ranking has to do with the supply chain, not quality. Tier 1 suppliers work directly with OEMs, often providing subassemblies. Tier 2 suppliers provide Tier 1 suppliers. Tier 3 suppliers supply Tier 2 suppliers, often with raw materials. Let's say the subassembly is a power window mechanism. The Tier 2 supplier might provide the brackets, motor or electronic control module. The Tier 3 supplier might be the company supplying the chips for the electronics, or steel for the brackets. In the case of DuPont, as a paint supplier selling directly to OEMs, it was Tier 1. It also sold coatings and polymers to Tier 1 companies, making it a Tier 2 supplier, and a lot of polymers were also sold to Tier 2 suppliers, making it a Tier 3 supplier.

It’s been a very long time since I read such a comprehensive review on a new car. Harkens back perhaps to Car of the 70s. Though they would likely have been more complimentary due to the McLarens Englishness. Great work.