George R.R. Martin's Going To Need Some Space Spiders Pretty Soon

Warning: contains mild spoilers for certain aspects of George R.R. Martin's "Song Of Ice And Fire" series, a brief non-spoiling discussion of John Fowles' "The French Lieutenant's Woman", and severe spoilers for David Wingrove's "Chung Kuo" series.

I have a few friends who are in the middle of slogging through the "Game Of Thrones" series of books. I finished A Dance With Dragons, the fifth and most recently published of seven planned volumes in that series, last year. Although the first three books are page-turners of a kind, the last two are little more than rambling travelogues through imaginary lands that spend a combined two thousand pages --- more than War and Peace by a long shot --- adding unwanted new characters, increasing the complexity of plotlines that were already sufficiently complex, and putting existing characters into improbable situations.

The overwhelming feeling that one gets from Dance is that Mr. Martin has absolutely no idea how to end his story. How did he get there --- and what's the worst possible ending to all of this? The simplest answer is this: Mr. Martin shouldn't be in any trouble whatsoever, because he should have thoroughly and carefully plotted the entire series out before selling the first book, the same way all those Star Wars Universe novelists presumably do, and the same way Brian Herbert presumably does every time he sets out to further sully the memory of his father's literary accomplishments. Yet I'd venture to guess that this is not the case at all, that Mr. Martin didn't plan on this particular series lasting much past two or three books, and that he's effectively written himself into a corner from which there's no easy escape.

How does something like that happen? John Fowles, in his postmodern meta-novel The French Lieutenant's Woman, suggests that characters in the hands of an author have "free will" and

This is why we cannot plan. We know a world is an organism, not a machine. We also know that a genuinely created world must be independent of its creator; a planned world (a world that fully reveals its planning) is a dead world. It is only when our characters and events begin to disobey us that they begin to live.

Easy enough to say when your book has fewer than a dozen characters and only one relatively prosaic plot point to resolve. But when you have more than fifty primary characters interacting in complex fashion across a world landscape which is effectively the size of Earth's Western Hemisphere, that sort of free will, that sort of disobedience, doesn't add life to a work of fiction. Rather, it destroys momentum, which is what mega-books have in place of life. In The French Lieutenant's Woman, the "free will" that Charles Smithson expresses upsets a minimum of applecarts. Compare that to, for example, the kind of mire into which the Daenerys-Targaryen-as-Khaleesi plotline has sunk by the end of A Dance With Dragons. Is Mr. Martin giving "Dany" the same freedom to roam that Mr. Fowles gave Charles? If so, it's had a much more destructive influence on the work.

I think Mr. Martin is suffering from a bit of mission creep with the "Song Of Ice And Fire", on at least two fronts. The first is obvious: what was supposed to be a relatively tightly-plotted revisionist look at fantasy literature has turned into an absurdly expansive exercise at world-building that raises two questions for each one it answers. Consider this: It's made plain that the conquering of Westeros would be a trivial matter for any Essos-based minor potentate, an effort so minor that it could be accomplished on a purely commercial basis by purchasing Unsullied and renting a relatively minor mercenary fleet. Add in the fact that no effective farming has taken place in Westeros for years by the time the fifth book wraps up, with most of the remaining soldiers either starving or in some sort of zombie mode, and it's frankly inexplicable why nobody's bothered to simply go over there and clean house.

The second kind of mission creep is perhaps less easy to spot, but it's just as troubling. The first few "Game Of Thrones" books have the even pacing of a good history book, perhaps mixed with a little softcore porn from time to time. There's no great art being made here, but let's be honest: you don't buy a multi-volume work of fantasy fiction because you're expecting A Farewell To Arms. You buy it so that flight from LGA to LAX or the unexpected night in an empty hotel will pass smoothly. Had Mr. Martin died after finishing the third book, I'm pretty certain I could have finished the series no problem. Easy as pie. You have Dany pop back across the ocean with some big dragons, the White Walkers cross the Wall as Winter arrives in full blast. Everybody teams up to fight off the White Walkers, who eventually retreat when winter passes. In their wake we find the dead bodies of all the annoying characters. Dany marries a rehabilitated Jamie to end the war and settle their child on the Iron Throne. Or we let Jamie die defending Dany somehow and put Jonah Mormont in the saddle. If you want it wrapped up with a bow, have them adopt Arya Stark as the heir apparent.

At some point in the fourth book, however, Mr. Martin started to feel compelled to write a bit. And his idea of writing seems to primarily consist of describing meals and travel and mind-numbing length. The same guy who fits the so-called "Red Wedding" into a handful of pages spends ten times that describing a trip down a foggy river. If you decided to rank the importance of characters by the amount of time devoted to them, you'd think that Ned Stark was approximately as important as, say, Ser Balon Swann.

All this writing is taking the steam out of the books. Each one takes Martin longer to finish than the one before, and fourth and fifth episodes have made the eventual end more difficult to wrap up neatly, not less. I've already resolved that I won't read the sixth book when it comes out --- a resolution I'm frankly not very likely to keep, but one that I'll certainly regret not keeping a few hundred pages in.

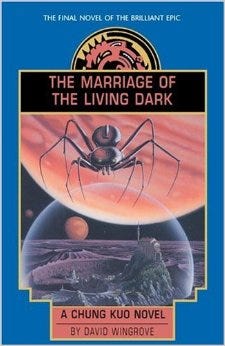

The whole situation reminds me of nothing so much as David Wingrove's Chung Kuo series. The first few books, which deal with a far-flung future in which the Chinese have taken complete control of the planet, are brilliant and amusing, gritty and realistic. It's one of those rare future worlds that is both completely possible (minus a few technological hand-waves) and utterly fascinating. By the seventh and supposed-to-be-final book, Days Of Bitter Strength, the plot's slowed down considerably and the pages are thick with extra characters and inexplicable happenings. It ends with the typical "conclusion, in which nothing is concluded", and it's not so bad that it completely undermines the series.

As fate would have it, however, Mr. Wingrove's contract obligated him to an eighth book. (Or he needed the money, or there were other factors; nobody's quite sure.) Rather than describe the result myself, I'll let I. J. Parnham explain:

So it comes as something of a shock to learn that DeVore, one of the most compelling and complex characters I've ever come across in fiction, isn't a man at all, but is in fact a giant immortal pan-dimensional space spider from the planet Zob, who came to earth for the sole reason that he wanted to roger the living daylights out of as many earth women as possible. But then he forgot he was a giant immortal pan-dimensional space spider from the planet Zob - as you do - and so he just hung around for thousands of years messing up all earth history in his quest to get laid with as many different types of women as he could find. It therefore follows that all the wars and atrocities and rebellions everyone committed for the last 2 million words weren't done to change history, in fact every major earth conflict in all history wasn't the result of anything we mere earthlings did, but were in reality only carried out because a giant immortal pan-dimensional space spider from the planet Zob was fascinating by the way women's jiggly bits move...

The final chapter is even more bizarre and takes place in yet another reality, I think, although at this stage the author appears to have lost track of which reality is supposed to be the real one. In this reality the last-best-hope-for-mankind generational spaceship that left Chung Kuo earlier arrives at its destination. People who died in earlier books are on the ship as well as people from our reality and people from the defunct reality who did actually get on the ship as well as people who missed the ship. Everyone stands around being a bit confused by it all. Giant immortal pan-dimensional space spiders from the planet Zob get a mention as something they might do well to avoid when forging a new life on a new planet. Then everyone wanders off to pick flowers and the book ends.

And there you have it. It's almost impossible to find that eighth book for sale anywhere; supposedly this is due to the publisher being horrified by it and shorting the print run. Wingrove's fans, by and large, have taken the approach that the eighth book is "not canon" and therefore didn't happen.

What was Wingrove's intent with The Marriage Of The Living Dark? Was he punishing the publishers? The readers? Himself? Was he just sick of the whole thing? Was it a brilliant meta-statement on the impossibility of maintaining a coherent and logically plotted universe across eight books? Or --- and this is obviously the most horrifying idea of all --- did he think that the space-spider thing was a good idea? Was he so divorced from reality at that point that he thought that his newest great concept was as good as his old great ideas?

The frightening thing about the space-spider ending is that George R.R. Martin is coming perilously close to needing something like that himself. He has two books left in which to resolve the plotting issues of five previous ones. The fan base demands a complete wrap-up; they won't be satisfied by anything that doesn't explain everything from the White Walkers to Strong Belwas. I have to think at this point that they won't get it. Instead, they'll get a pretty strong dose of Anyone Can Die, a staccato disappointment of lethal endings sprinkled across two thousand more pages of travelogue and meal descriptions. The last people standing will be the winners --- and it will probably be somebody who didn't appear until the final few books, just to add some insult to the injury.

It will amount to cheating the reader a bit, but the HBO series and the resultant explosive jump in sales of the earlier books have financially insulated the fellow who once wrote Sandkings from any sort of need to maintain reader goodwill. Shame, really.

Not just for us. Mr. Martin's pretensions to art in the more recent books, along with the remarkably slow pace at which they're being written, make me think that he has genuine concerns about wrapping everything up just right. I have my fingers crossed for him to do it. But even if he doesn't, there's still hope of a sort. Twelve years after he infuriated the readers with the eighth Chung Kuo book, David Wingrove returned with a "re-imagined" series based on the originals. It's supposed to stretch to twenty books, with seven already out. How do you make twenty books about anything? Remember this: Ulysses described the events of a single day.