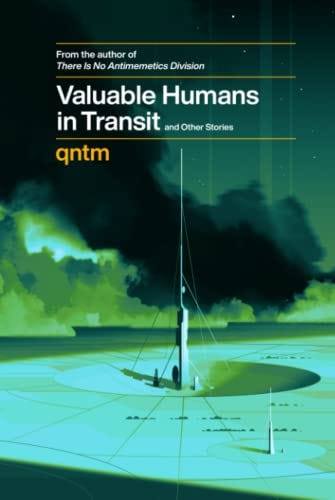

Book Review: "Valuable Humans In Transit", by "qntm"

Free to read for all subscribers

Forty — forty! — years ago, William Gibson wrote Neuromancer and formalized a genre of science fiction writing called “cyberpunk”. You can argue endlessly about the actual origins of cyberpunk and its current status; did it die when Neal Stephenson wrote Snow Crash? Or when William Gibson wrote Pattern Recognition, showing that the present day had become cyberpunk in all but name? Some people say that the end of legitimate cyberpunk was heralded by Orson Scott Card’s “Dogwalker”, since Card was the biggest kissless virgin nerd in sci-fi history and therefore the existence of a “Cyberpunk Card Story” removed any possibility of the genre ever being cool again.

Short-lived the genre may have been, but it had a profound effect on mainstream science fiction not dissimilar from what punk music did to rock-and-roll. Mainstream writers aped Gibson’s caustic and hopeless authorial voice but couldn’t master the stylistic tricks and sense of story that kept Neuromancer and its successors from falling to the level of meaningless dystopian trash.

In hindsight, I would suggest that cyberpunk is defined by a single trait; it aims to shock the reader with the everyday banality of a frankly evil future by extending current trends to their logical conclusions. Neuromancer was a bleak extrapolation of Apple ][ computers, modems, arcade games, and bulletin boards, written by someone who had no experience with any of that stuff. I believe that the closest thing to a modern cyberpunk classic is Glasshouse by Charles Stross, which offers a nightmare look into a universe where the fabled “brain scan” is an everyday occurrence and people will prepare for a first date by forcing fully-self-aware copies of themselves and their potential date to live an accelerated fifty years together inside a quantum computer beforehand. The plot twist of Glasshouse is so depressing that I can’t in all good conscience recommend you read the book — unless that’s your thing, of course.

Sam Hughes, known as “qntm” when he writes science fiction, is a legitimate heir to the cyberpunk tradition whose taste runs towards the morbid short story. Valuable Humans In Transit occupies a conceptual space somewhere between the ultra-near-term timeline of the newest William Gibson novels and the spacefaring societies of Charles Stross. It starts with “Lena”, which you can read for free at the author’s website. It is written in the style of a Wikipedia entry:

MMAcevedo (Mnemonic Map/Acevedo), also known as Miguel, is the earliest executable image of a human brain. It is a snapshot of the living brain of neurology graduate Miguel Acevedo Álvarez (2010–2073), taken by researchers at the Uplift Laboratory at the University of New Mexico on August 1, 2031. Though it was not the first successful snapshot taken of the living state of a human brain, it was the first to be captured with sufficient fidelity that it could be run in simulation on computer hardware without succumbing to cascading errors and rapidly crashing…

MMAcevedo's demeanour and attitude contrast starkly with those of nearly all other uploads taken of modern adult humans, most of which boot into a state of disorientation which is quickly replaced by terror and extreme panic. Standard procedures for securing the upload's cooperation such as red-washing, blue-washing, and use of the Objective Statement Protocols are unnecessary. This reduces the necessary computational load required in fast-forwarding the upload through a cooperation protocol, with the result that the MMAcevedo duty cycle is typically 99.4% on suitable workloads, a mark unmatched by all but a few other known uploads. However, MMAcevedo's innate skills and personality make it fundamentally unsuitable for many workloads.

This combination of the first and eighth paragraphs is enough to induce subtle horror in any working programmer: oh shit they are booting self-aware people on silicon and forcing them to work on menial tasks until they go insane. The finest and most unsettling accomplishment of Valuable Humans In Transit is that it seamlessly adopts our current and astoundingly moronic concepts of computing infrastructure — Docker, Kubernetes, endless shells of virtualization and replaceability — to the human condition. Those of us who watched computers go from massive mainframes so individual that most of them were known by a specific name to mere “images” that most of the time don’t even get the courtesy of their own dedicated hardware will have little trouble envisioning the same thing happening with human beings.

It’s an obvious insight, yet it’s also one that just about nobody seemed to have had prior to a decade or so ago. The AIs of Neuromancer and its sequels are unique individuals with genuine value. Until Stross and his cohort arrived, sci-fi writers were generally unwilling to confront the idea of valueless humans. It was always obvious, for example, that the Star Trek transporters killed people on the transmit end and created them on the receive side, but it was like everybody had a firewall in their minds about the implications of that. No longer; the section of Glasshouse where soldiers are cutting heads off refugees in order to “save” them removed our collective innocence on the matter.

The longest story in this collection is more properly termed a social experiment. You can read the original online version here; it was “written” on Twitter. The purpose was apparently both to stir false memories of a “Google People” service and to suggest the existence of a genuinely disturbing Google experiment in replicating consciousness.

Sold in a pocket-sized print format that perhaps unwittingly emphasizes the “snackable” nature of the stories within, Valuable Humans in Transit is worth your time if you’ve ever enjoyed anything approaching sci-fi. Which is good news, because the genre has gone downhill at warp speed in the past two decades. The average sci-fi book nowadays is an overly-long “episode” in some imagination-deficient “universe” that contains 25 hastily-written and entirely-unedited rambling variations on a single theme. Even the mighty and innovative Charles Stross is no exception; a quick check on Amazon shows that he has written dozens of books in something called “The Laundry Files”.

PROTIP: there is no story in the world that cannot be effectively told in the space of three 250-page novels. Anything more than that is either a soap opera or a Major Literary Event along the lines of Moby-Dick or a sprawling Barth (no relation) novel like The Tidewater Tales.

It doesn’t help, of course, that the current sci-fi establishment has become obsessed with issues of race, gender, sexuality, and identity, with confirmed idiot NK Jemisin as the poster child for every bleating bit of it. But that’s not the biggest problem facing science fiction. Rather, it is this: Cyberpunk, like a computer virus, infected the rest of the field to the point where all the really intelligent people in sci-fi are writing mirthless dystopian garbage because that’s the only thing that feels “real” to them. Therefore Valuable Humans in Transit feels extremely real, because while its head is in a Crapsack Future, its feet are firmly in our Crapsack Present.

This utter seriousness, executed by an intelligent and committed person, is in fact too depressing to be consumed in bigger-than-snackable amounts. What science fiction needs is not more of this, regardless of the skill and thought involved. We need starships and blasters and witty robots and scary aliens. Failing that, we’d settle for relatable antiheroes facing overwhelming odds. Which was the secret heart of Neuromancer, you know. Strip away the arcologies and Ono-Sendais and it’s just a Joseph Campbell story under neon light. Could anyone among us bring that original expression of cyberpunk back to life, with just a soupcon of cynicism and isolation rather than a full tureen of it? I doubt it; we’re just not wired that way anymore.

Well... While I liked some of the cyberpunk out there, I don't like writing cynicism. It's easy to bring people down, bringing them up is harder, and more rewarding.

I did have a hard sci-fi novel traditionally published a few months ago, BTW, and it was up for the Prometheus Award - though sadly I didn't win (though an acquaintance did, so not going to complain). My scifi, nor pretty much any of what I write, are obsessed with race or gender or any of that nonsense and yes, I'm not a fan of 'Token' either (note, I did not say Tolkien). Which is probably why I do so well.

Now as to Cyberpunk.... I'm a week or so away from finishing my next tradpub novel for Baen. Once that's done, I've got a little something different that I'm going to write. I'm looking to combine cyberpunk and another similar genre and put it all in a post-apocalyptic world. As I've taken two 'dead' genres and pretty much resurrected them I'm kinda hoping for a third. But again, it's not gonna be a downer and cynical type story - thought it's definitely going to come out of that sort of setting.

The biggest problem with a lot of this are the tradpub gatekeepers, and the simple truth that MOST indy writers, only write to market and only write to already successful markets. I'm one of the few folks out there always looking for something new. Because I get bored. I also think that if it's done correctly, the market is ripe.

Joseph Campbell and the hero's journey will always be with us. Because people love that story.

As for any story being told in three 250 page books? Any story can be told in a hundred words if you got the skill and think about it enough. It's not the story so much as the -ride-. I wrote an 18 books series that perhaps could have been told in less books (I forget how many words that is - over a million - we don't go by page numbers as you can trick those quite easily) but it could NOT have been told as well. Nor would it have made me as much money.

Nor would my fans have begged me to write a sequel (up to 8 books at this point - yes they waved money at me and I'm weak).

There is more to writing a book than telling a story.

As comedians love to say: It's ALL in the delivery.

OK. A literary post. Please excuse this intrusion into your SciFi stuff but I just read my first Cormac McCarthy novel (no, I don't know what took me so long) and I have a question.

"The Passenger" involves many locales from New Orleans to Knoxville to spots out west to Ibiza. All are areas that have figured in Cormac's life. The outlier is Akron. Akron is featured and I can't figure out why. Growing up in a suburb of Akron this particularly interests me (Well....the whole book interests me. It will be read multiple times). Do any of you learned gentleman have any ideas on this?

Sorry. Please carry on.