BMX Basics: "Squid Is Squirrelly"

A few of you know that I wrote for "Bicycles Today" magazine from 1990 to 1998, and that I maintained the "BMX Basics" website from 1997 to 2004. For your amusement and mine, I'll periodically be resurrecting some of the old columns from back in the proverbial day. This one, originally published in "Bicycles Today" in 1991, was a semi-fictional, present-tense account of a young rider's first race. I was eighteen when I wrote it. However, I've resisted the temptation to edit it. Thanks, as always, for reading. And please read the note at the end, even if you skip the story --- jb

The first sensation Squid is able to consciously locate is the feeling of the padded top tube of his 1985 1/2 Redline 600c precisely, and painfully, finding the space between his legs and nestling there contentedly.

Dazed, he stares for a moment into the back of his Haro Series 1-B number plate, as his knees drag perilously close to the ground. All around him, dust forms an axle-high layer of brown clouds, and everyone disappears from his field of vision, which is centered around his handlebars. The momentum of his bike carries him down the Pataskala "Phase IV" BMX track's starting hill. Three inglorious words form in the back of his mind, waiting to be set free by some sort of...

"Yep, Allen's doing the Top Tube Tango, and further on down the track we got..." - public announcement.

Whole eons of time seem to slip by as Squid struggles to rise from the position of the Top Tube Tango, that is, face in the bars, knees nearly on the ground, and legs to the sides of the top tube. On his right, past the starting hill's grassy side, is a large, metallic set of stands for the audience that crowds the track on the weekends. To the left, the large, wooden announcer's tower holds two fat, balding middle-aged men who have volunteered for the job of sagely commenting on the pratfalls of greenhorn racers such as Squid. Odds and ends that Squid, never having been in the tower and, indeed, only being here at the track for the second time, cannot possibly imagine, clutter the tower's small floor space.

The track itself goes straight as anything one could imagine for about five hundred feet, at which point it generously curves to the left and winds its way back by the announcer's tower through a succession of S-curves and 'cereal bowls'. Around the track, towards Creek Road and the gravel parking lot, stands a brown wooden fence on which the spectators who have a personal interest in this particular fence lean. The rest, waiting for their own progeny or pals to compete, have retired to the apparent comfort of blankets and picnic baskets a yard or so behind, or with enough time, have gone to the dirty white building behind the starting gate and staging area that house the snack bar and Pataskala's only video arcade. Squid sees this all, dimly, as he fights for a proper perch on his reluctant Redline.

By the time he reaches the bottom of the starting hill, he is up and pumping in furious pursuit of the seven riders who have been lucky enough to not run into the starting gate before it dropped. The first jump lies halfway down the straightaway. Squid, who has seen the local hotshots, the kids who have earned spots on the Phase IV team, do double cross-ups or kick-outs towards each other, very stylishly, over it, chooses instead to honor the jump with an accidental lifting of the front wheel, which wobbles until he slams it back on the ground decisively and rides down the hill's backside.

Approximately twenty feet ahead of him, Squid's first victim, fellow member of the 14 Beginner class, looms. But Squid can't quite seem to close the distance as the pack, trailing him behind, noisily sweeps into the first turn.

The noise a pack of inexperienced, frightened, and yet utterly determined Beginners makes is perhaps the root of the sport's charm. Of course, mechanical sounds form the background; the imperfect squeak of misaligned crank, chainwheel, and chain hiss and clank through the racer's immediate field of hearing. The sixteen tires, eight front and eight rear, most of them either Tioga's popular Comp III model or some clever imitation made side-by-side with the original product in the same Taiwanese factory but lacking the three-color ink print that would justify the $8.99 mail-order price, thrum against the dirt. If the track is nice and dry, these tires may even roar a bit as they do on concrete.

Above the mechanical background, one hears the grunts and curses the riders spit through their dusty, required mouthpieces as they attempt to fight their way through a continually shifting pack. Beginners and novices constantly make noise when they ride, not having learned to pace themselves through the length of the track, grunting near its beginning and gasping near the end.

The Experts are missing that noise. They are so perfectly matched that they all hit the first jump together, pedaling in an unearthly eight-man chorus line free of all but the sonically rotating clicking of their three-piece cranksets and that ever-present thrum, until the pecking order is established in the first turn and the pack spreads into a gentle follow-the-leader. These experts usually seem content to let the order in which the class enters the first turn determine the character and finish of the race. Squid had thought, watching the Experts earlier, that when he became an Expert he would fight, shove, and move up in line, just like the Beginners do, not realizing the supreme, unseen effort involved in that line of silent, hardworking Experts.

A step-up double jump mars the perfect, leftward, 180-degree first turn. Squid copes with it by hitting the brakes and letting his body dangerously jar the handlebars and seat as inertia seems to take him away from his Redline, which is determined to remain earthbound. Down the back of the jump he remembers himself and pedals furiously into the first of the S-turns. Miraculously, his exertions are having an effect, because the last rider in the snarling and shifting pack is growing ever closer. Around the fourth or fifth spot in the moto, there is a collision which causes a rider to slip a pedal, and the pack casts him backwards into seventh place. The yellow helmet of this rider dips when he, as all the magazines advise the young Beginner to do, looks under his arm to briefly observe Squid, rather than looking back over his shoulder.

Squid is there, six or seven feet back, and he attempts to frighten his prey by pulling a power wheelie, which removes an essential element of control from the short-wheelbase Redline, now desirous of pitching Squid from its back. By throwing his body forward, Squid avoids this consequence, but the damage is done. He is now ten or twelve feet from a new seventh-place rider, a recent victim of Yellow Helmet's apparently superior passing technique. A small set of double jumps opens up onto a right-hand, right-angle turn, and then there is about forty feet to the finish line. The first-place rider jumps the doubles successfully, his increasingly desperate pursuers electing to take the faster, grounded, way across.

Squid has read in BMX Action that "gettin' gnarly is almost as important as winning races," and, ever mindful of this, attempts to clear the doubles, to win some sort of attention even though he is dead last. As well as dead last, however, he is dead tired. Sadly, he lands square between the humps and slips a pedal. Placing his foot back where it should be, he makes a run for seventh, but he is at least ten feet too far back. Making a right turn after the finish line, stomach and throat heaving from his effort, Squid falls sideways down on the grass, still connected to his bike, seeing as if for the first time the impending darkness of the seven-thirty sky. He closes his eyes, ignoring his mom and little brother running up towards him. Trying to breathe, he imagines his number plate, which reads 27A, crossing the line first and securely, but he knows that it was, instead, the 24B of the track's hotshot 14 Beginner. Thus, in August of 1986, was Squid introduced to racing.

Twenty or so minutes later, Squid, nursing a Coke in a plastic cup from Pataskala Phase IV's all-encompassing snack bar and arcade, leans against the previously mentioned wooden fence, and shouting enthusiastically, cheers his little brother on to an easy victory, his third such in the three heats that determine the overall finish placing out here in the grassroots of BMX. His brother, already displaying at age eight the broad back and confident demeanor that have so far escaped Squid, has ridden his Redline, which is also Construction Yellow, to three straight victories, while Squid has received two consecutive last places. His second race had afforded him a better start, but feeling mired in mud, he couldn't maintain pace and the rest of the pack had simply sprinted on and left him behind. As his brother humiliates his lone opponent out there on a track that must seem never-ending to him - unlike the hotly contested 14 Beginner class, the 8 Beginners had only drawn two entrants this Friday night - Squid dons his Bell Pro-Plus helmet and, seeing his brother cross the line safely, leaves him Mom to dispense the night's third set of congratulations as he trundles over to the staging area. On the way over, he throws what is left of the Coke into a trash can and decides to tie his shoe. As he leans over to do so, the dusty chrome of the Redline's rear triangle fills his eye, and Squid is seized by a sudden, almost nauseous, surge of joy that such a bike might be his, despite his inability to show any of the signs of a promising Beginner.

Now Squid climbs the starting hill. He lines up, unnoticed by the seven other riders, who have dismissed him as a non-contender, a poser, never to return to Pataskala after having his tail kicked around the track for the third straight time. Now the lights, the noise, and Squid pushes hard, moves into seventh place around the first turn, loses his balance over the doubles and slips to eighth. The first S-turn presents an opportunity. Squid shoves inside and by the seventh-place rider, who, shoving his front wheel furiously into Squid's right leg, attempts to take Squid out but succeeds only in hitting the dirt himself.

Squid is firmly in the pack, thumping, grunting, and cursing with the rest of them. The noise removes his ability to think and all the advice he has read and received flies out the window as he puts his head down and pumps furiously through the cereal bowls. Up front, there is a shove and a noise that closely resembles a minor car crash, and Yellow Helmet, his previous nemesis, seems to magically appear before Squid on the evening-darkened ground, writhing in pain and trying to regain his footing, a dark shadow rendered evil by helmet and visor.

Squid panics, dives around and up the high side of the last berm, rolls uneasily across the doubles, and, swinging his head from side to side like a wounded animal in an effort to gain just a little more power, crosses the line less than five feet behind the fifth-place rider. Although he again dry-heaves on the worn grass past the announcing tower, the dusky light has acquired a new kindliness for him, so beautiful not to be dead last.

* * *

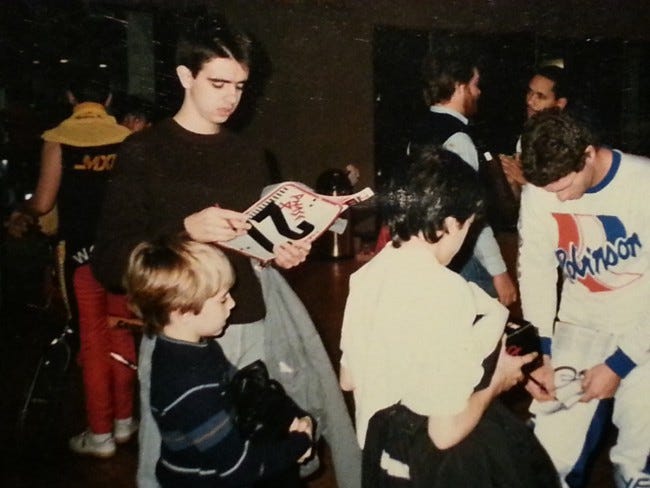

There are three kids in the second photo above, getting their number plates signed by Greg Hill at the 1986 Christmas Classic. The tall one with his mouth hanging open like a moron --- that's me. The little blond-ish kid is Bark M, of course. The third one, facing Greg and holding a Dia-Compe brakeset in a box, is our friend Bobby Sochor. Bobby was four months older than I was and we lived in Riverside Green together from 1985 through 1988. He was born with scoliosis and a few other health problems. He never grew much past five feet tall. Despite that, he started racing right along with me and Bark, swept up in my enthusiasm and wanting to be part of what we were doing. He had the same bike that I had, a Redline 600c, in the same color. He didn't have much luck and he got hurt a lot so he quit before the 1987-8 season. The older teenagers and high-school graduates bullied him a lot when I wasn't around and, to my sorrow, sometimes when I was.

In the years after high school, I lost touch with Bobby. After graduating from Miami I ran into a friend of a friend who told me where Bobby lived so I went over to see him. He was the same humorous little guy I always knew. He told me he was going into teaching and that all the kids would be taller than he was. I told him we'd keep in touch. We didn't.

Robert Sochor died October 13, 2005 of long-term complications related to his childhood illnesses. He was remembered as a popular and effective teacher, well-liked and influential in the lives of his students. Sometimes I like to think back on the times he, Bark, and I spent riding our Construction Yellow BMX bikes around Riverside Green. I'd like to think that I'll see him again some day, in an afterlife of sorts, though I know in my heart that I will not. In a way, this blog is his as well. Goodbye, Bobby.