Advertising To Your Worst Instincts

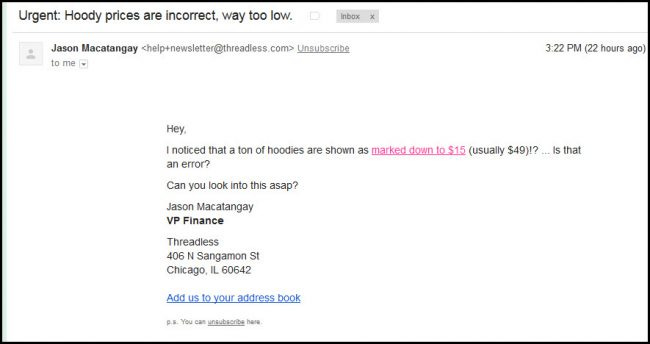

I got this email yesterday morning. For a brief moment, I was confused, in part because I've written and deployed a lot of online commerce stuff for people over the past fifteen years and this is exactly the sort of communication I used to get when things went Very, Very Wrong. Once I realized it was from Threadless, the people who make many of the odd T-shirts I've worn on this and other websites, and I've had a couple of customer-service discussions with their reps in the past, I wondered if perhaps somebody had mis-typed my contact into Outlook.

Once I got my head out of my ass, of course, I realized what you probably realized immediately: this is an advertisement. But what's being communicated here, both about Threadless and about us?

Online shopping is a profoundly disturbing and disruptive social experience. For pretty much the entire history of commerce, we've done it either face to face or through the written word. Both of these methods are profoundly human interactions; if you doubt that, then go back and read various letters between tradesmen or even between, say, President Eisenhower's staff and the people at Rolex. Hundreds of thousands of Americans wrote heartfelt, handwritten missives to Sears Roebuck inquiring about farm products or children's toys.

When my brother and I opened Squidco, my mail-order BMX bike shop, in 1992, I was surprised at how quickly we came to know and like many of our customers. I had a few guys who would call me for no reason, just to talk about bikes. There was one fellow who sent me pictures of his bikes and long letters about his local trails/race scene about once a month. I still have those photos; a crazy-eyed, long-haired dude with matching chrome S&M race bikes and thick veins bulging out of his arms and forehead.

"Getting and spending," Wordsworth wrote, "we lay waste our powers." He wasn't wrong, yet there was something to be said for the human side of every sales transaction. Until now. Online shopping is completely impersonal, handled by expert systems, robots, and even drones from start to finish. At companies like Amazon, there is no human interaction other than the picking of items that are difficult to sort or load into a box by machine. But even smaller companies often no longer handle anything relating to the purchase transaction itself; their expert systems simply give them a list of customers and what to ship in each box.

This is where things get dicey. Most of us have a profound aversion to knowingly cheating another human being, even if that human being is just doing a job as an order-taker on the other end of a phone. But cheating a machine? Who cares! Thus the cottage industry of "dealfinder" websites that purport to show you how to "stack deals" and get products for prices much lower than their vendors ever intended to charge.

The early online shopping systems were fair game for this stuff; you could use multiple coupon codes, pull things in and out of shopping carts to trigger discounts that then did not automatically go away, and so on. Some firms, like Sierra Trading Post, encouraged the process and would put "easter eggs" in to give you absolutely outrageous deals once in a while. Most online sellers, however, simply were not sophisticated enough to understand what was being done to them.

As long-time readers of this site know, I am obsessed with saving money on things I don't really need and I was a compulsive deal-stacker back in the day. I've had orders canceled by vendors, I've have orders that were never filled, I've even had vendors who made additional charges on my credit card to bring the total price back to what they though was "fair" for the transaction. I don't bother deal-stacking anymore, largely because I'm no longer working in environments where I wear, and wear out, a lot of expensive clothes. But I still remember the thrill of getting an Armani sportcoat for $209 and stuff like that.

This Threadless email --- you see, we've finally returned to the subject at hand! --- is meant to entice the deal-stackers. And it's a shrewd play on human emotions. If you got an email from Threadless saying "$49 Hoodies marked down to $15!" you'd assume that the hoodies in question were unwanted junk. But an email that appears to alert you to a pricing glitch? Now, gentlemen, you have my interest. And I'll have a much more favorable pre-opinion of the products when I start shopping. These aren't fifteen-dollar unwanted throwaways! These are the same hoodies that other people are paying $49 for!

Truly, it's a smart advertising campaign, but I don't like what it says about Threadless or its customers. It implies that the company is comfortable with social manipulation and it further implies that the company has a low opinion of its customers' morality. It also sets up an expectation in the minds of those customers that the product really shouldn't be worth anything more than $15.

I'm reminded of the shirtmaker Charles Tyrwhitt, which started off by making relatively expensive Jermyn Street products in the United Kingdom. Tyrwhitt started experimenting with closeout pricing on some of his odder fabrics. The customers became addicted to that pricing. Before long, Tyrwhitt had moved production to Eastern Europe to lower costs to the point where he could make money on the sale prices. But since the new shirts weren't as good, the customers wouldn't buy until the prices went even lower. It truly is a slippery slope.

It's also probably the future. A bunch of psych majors writing deceptive ads to puppet-master customers into thinking they are taking advantage of broken online systems. A perfect metaphor for society. Stop this world, I want to get off. But I might grab a $15 hoodie first.